Description

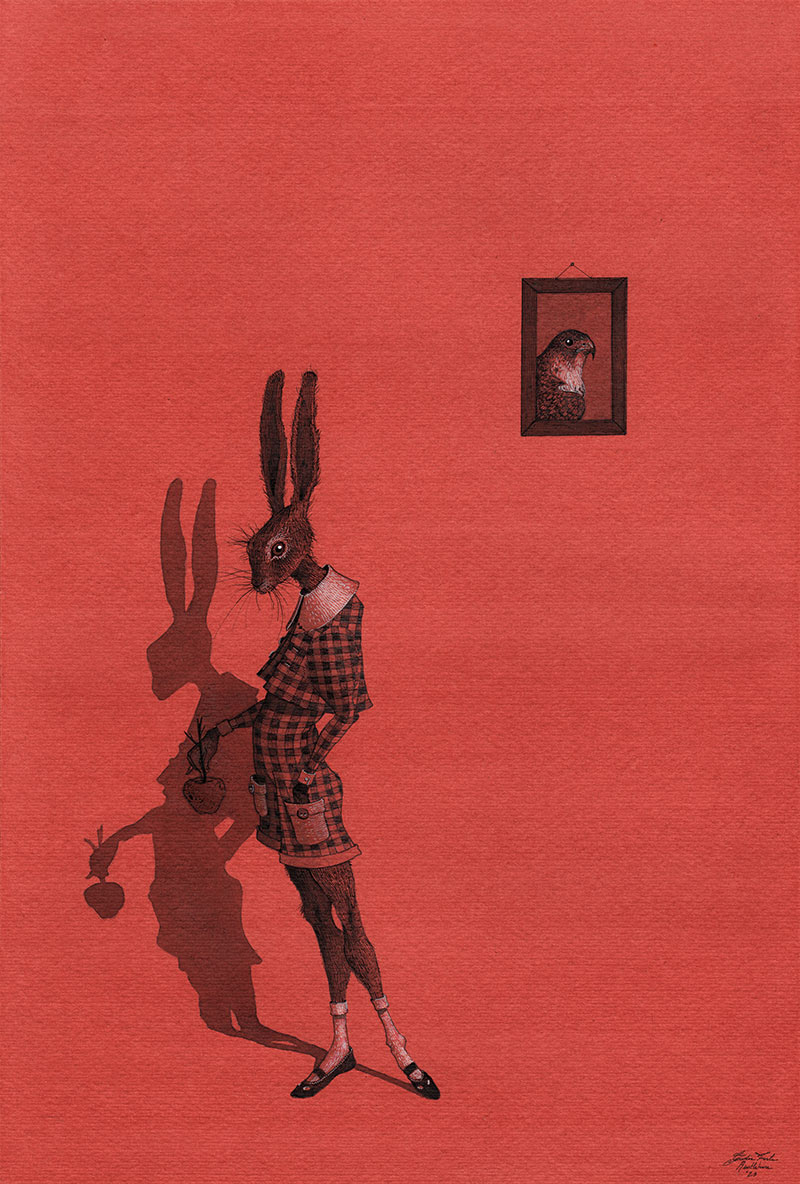

‘Idolatry’ by Rustlehare

Artist: Rustlehare

Title: ‘Idolatry’

Medium: Ink and acrylic on paper

Dimensions: 14.1″ x 9.8″

Framing: Unframed

Year of Creation: 2023

Artwork Will Ship From: Italy

About the Artwork:

To convince Hare to sell her house and move to the outskirts, it was a friend who had already been living there for years and to whom she confessed a strong sense of nostalgia over the phone. In the city, she had her sister, with whom she hadn’t spoken for a long time, and a couple of nieces whom she had seen grow up to the point where, enveloped by adolescence, they had become different and impenetrable. The speed with which she accepted the proposal pleasantly surprised her. She didn’t make a list of arguments for or against the idea. She sat at her usual caf , ordered some wateré with lemon, and recalled the afternoons at the cinema and the tangy taste of ice pops bought from a stall next to the ticket counter. Or maybe I’m mistaken, she thought, and added a spoonful of honey to her glass. Perhaps I no longer know what they tasted like.

She arrived in the outskirts in early June, and the air that filled the bus smelled of burnt hay and fertilizer. She wondered, as she let the sun fog her eyes, if she still had a connection with that shadow of a hare, crouched in the grass. Looking beyond the hedge, all she saw around the garden were more gardens and hedges, houses, and more hedges, more gardens. There was no horizon higher than the canopy of a distant oak tree. Nobody else was there, except for her. Just a vastness of mown grass, and at night, the wind that tilted the trees, releasing from the meadows the same sound as the sea.

She saw her friend almost every afternoon. Sitting in the garden, under the dense shade of the ivy that enveloped the pergola, they indulged in the pleasure of affectionate and superficial conversations. One time Hare would recount an episode, and the next time it could be her friend recounting it, always the same,

and neither of them, with their hands forgotten on the tray of cookies, seemed to notice. Sometimes they would say goodbye after dozing off, and one of them, the first to open her eyes, would whisper the other’s name and touch her on the shoulder. The rest of Hare’s time was spent on the veranda, where she had a more comfortable armchair than the others. She flipped through the pages of the novels she had brought from the city, occasionally watering the flower pots, and discovered that beyond the hedge, that new boundary of roofs and trees, was becoming less unexpected every day. When her friend died, Hare found herself doing the same things for days, and then she started wandering away from the gardens, towards those wide streets on which the sun is free to fall and scorch the asphalt relentlessly. It was too late to reconsider a life elsewhere. The thought of the city appeared to her as a labyrinth, not of walls cut into an obsessive pattern, but of days entwined around the passing of individual hours. She would not return there. She imagined herself old, enveloped by the fresh scent of lime that the walls of the house had, and by the color of the dawn on the bedroom walls, the most beautiful she had ever seen.

One morning, after hating the idea of making herself breakfast, she ventured into town. She bought coffee from the only open shop, where besides eggs and fritters, fertilizers and revenue stamps were also sold, and she continued walking. Enclosed by a network of clear and scorching steel for the sun, she discovered the velodrome, the long dirt track from which the carrier pigeons took off, soaring into the sky, and she stayed to watch them disappear until lunchtime. Her routine for the following months was almost the same as that morning.

With a thermos filled with coffee, she headed to the track and laid a cushion on the grass to sit on. She watched the falcons. For hours. Sometimes she brought a book, the same book, or some sheets of paper to sketch words or short lines. She pretended to be distracted, and in her ears, the flapping of wings and the wind

became louder than any written word. There were falcons that, after some time, seemed to have grown fond of the sight of the hare. And as their shadow passed over her head, briefly taking her away from the sun, they fluttered their wings. The hare watched them as one observes a departing ship, with passengers waving and bidding farewell to anyone and no one.

One day Hare was called back to the city to assist an old uncle in the hospital, who was nearing the end of his struggles with old age. She stayed away from the outskirts for a couple of months. Upon her return, the flowers had dwindled into a tangle of exhausted branches, and the house had absorbed a stale, sweetish

odor from the wooden furniture. The hare sighed, dropped her luggage next to the couch, and lay down, surrendering to her fatigue, allowing her eyes to gaze into the darkness.

One morning, upon discovering buds on her flower plants, the hare decided to return to the village. She bought frothy milk coffee, fried and sugared bread, and walked towards the velodrome to see the falcons. Arriving at the edge of the field, behind the steel fence, she was greeted by the usual sight. The sky above her head was immediately overshadowed by the wide wings of a flying falcon. She settled on her cushion and began to drink the milk coffee, taking small, almost tasteless sips. She had brought her book, but she left it in her bag. At some point, around lunchtime, a falcon approached her, flying low beyond the fence. The hare didn’t pay much attention, at that moment it was as if she didn’t even exist, and she continued to gaze at the sky. “Hello,” said the falcon. The hare waved her hand to greet him. By now, the falcon was towering over her, and she couldn’t pretend to see anything else. “You like being here, huh? I’ve seen you, I’ve seen you often, even though you haven’t come lately. Here or elsewhere, it’s the same,” said the hare. “Yet, you come back here every day.” “Yes,” replied the hare, “maybe I’m less bored here, I think that’s why.” “You’re less bored here? That’s new,” said the falcon, shaking his body like a cloak. “We falcons do nothing but take off and return to this track, from Monday to Friday. We live this life and no other. Do you think it’s beautiful?” “I don’t know,” said the hare. “I also do more or less the same things. At home, I have a fruit tree. A few flower pots. In the morning, I light the fire and bake bread. In the evening, I read, listen to the gramophone, well, I just turn it on. And then I remember. I remember a lot.” “And what do you remember?”

The hare shrugged, looked at her hands. The falcon took a step back. “I get bored too,” he said, and surrendered to a slow, heavy movement that gradually took him flying far away. “He gets bored,” she said. “And he flies.”

The first thing that irritated her upon her return was the mess among the cushions on the couch. Then she noticed the dusty mantelpiece, with the faces of the decorative objects smiling and suffocating in silence. There were scattered papers near the table legs, on the floor. And dry soil on the carpets. Crusted polenta

pots and small pans were piled up on the stove, and from the kitchen window, she saw the weeds overgrowing the garden and the suffering apple tree, laden with fruits so ripe they seemed bloodstained.

“This is my coming and going, dear Falcon,” she said, and throughout the afternoon, until dusk, she attended to household chores. In the end, after putting away the scissors, she took a basket and approached the apple tree, where she discovered a larger fruit than the others, nestled deep among the branches. “It

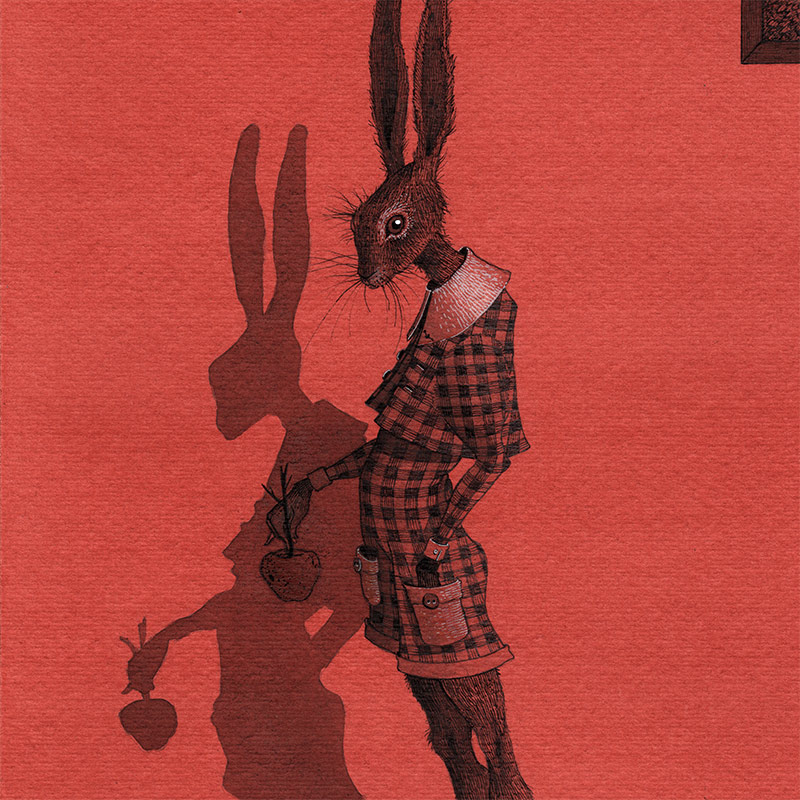

looks like a heart,” she said, and plucked the apple from the tangle of leaves. “Yes, it can only be the heart of the tree. I’ll make a cake out of it,” she said. She went back inside and turned on the light. Reflected in the mirror, on the wall in front of her, she saw the falcon. The falcon stood behind her, motionless, watching her. The hare didn’t turn around, she remained still, paled slightly. The apple, the heart, ceased to dangle in her hands. She thought, “You’ve discovered me. I was thinking of you. And also, you’ve discovered me, now you know everything about me. You know where my mornings begin and where my evenings end. Are

you here to watch me fly? Impossible, because I don’t fly.” The falcon’s eyes were black, and although they seemed to follow her wherever she wanted to go, they were actually motionless, and they were black and unknown, and they were black and glossy like split coal, and they were black like painted circles because they

belonged to the painting of a falcon. The hare averted her gaze from his eyes and noticed, in the absence of the body, the limits of the portrait, its position hanging right behind her. And outside that mirror, the hare remembered that she had never looked at it. She only knew the corner of the frame, a wooden angle that cast a red shadow on the wall in the afternoon. It was beautiful to watch the shadows of the sun. She turned on the gramophone, sat on her couch, and that evening, without doing anything else, she listened.

Tale of @unaportanellasiepe

About the Artist:

(Artist Bio)

Rustlehare was born in Milan in a foggy October 1989. She began her studies at the artistic high school, with a figurative address; subsequently she enrolled at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan where he obtained the 1st level academic diploma in Decoration. After a series of classical and rigorous artistic experiences, she decided to attend the Super School of Applied Art at the Castello Sforsesco, also in Milan, where she approached the world of illustration and publishing; a few years later she completed her academic training with the specialization in Graphic art. Later she taught Illustration at the Super High School of Applied Art of the Castello Sforsesco.

Today she organizes exhibitions of her work, training workshops, sells original works and prints and performs illustrations on commission, under the pseudonym of Rustlehare.