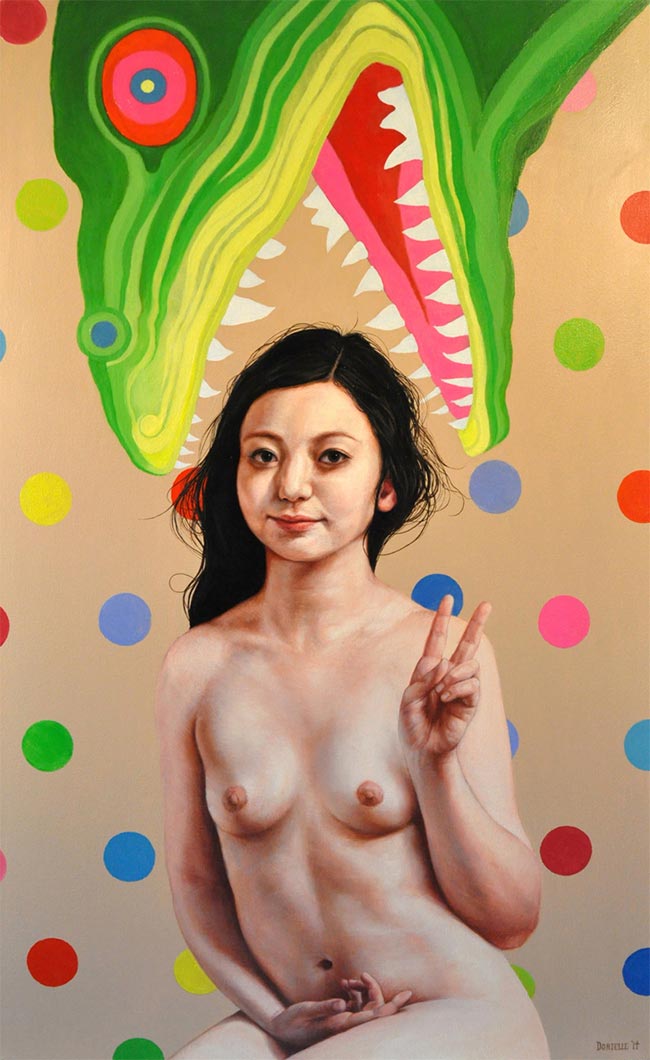

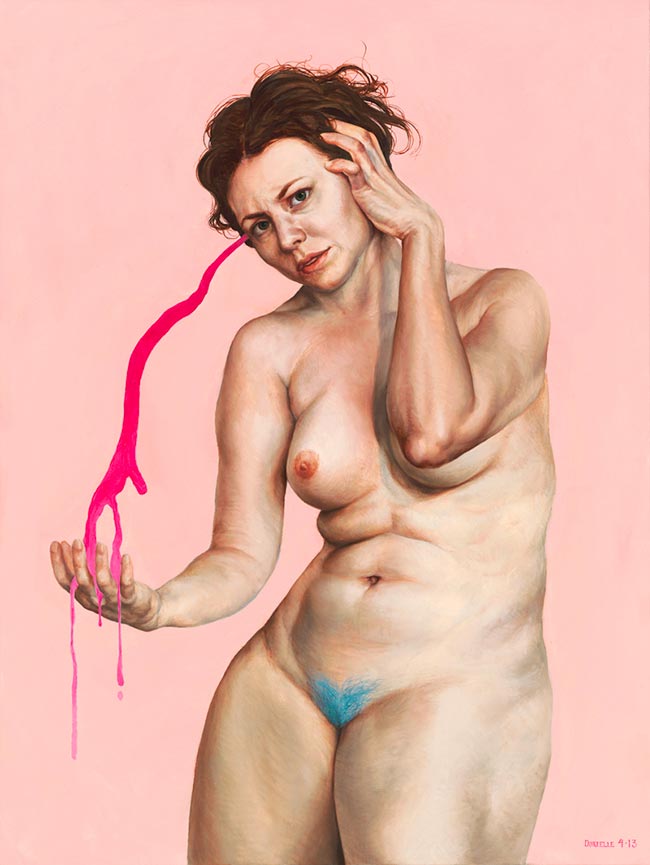

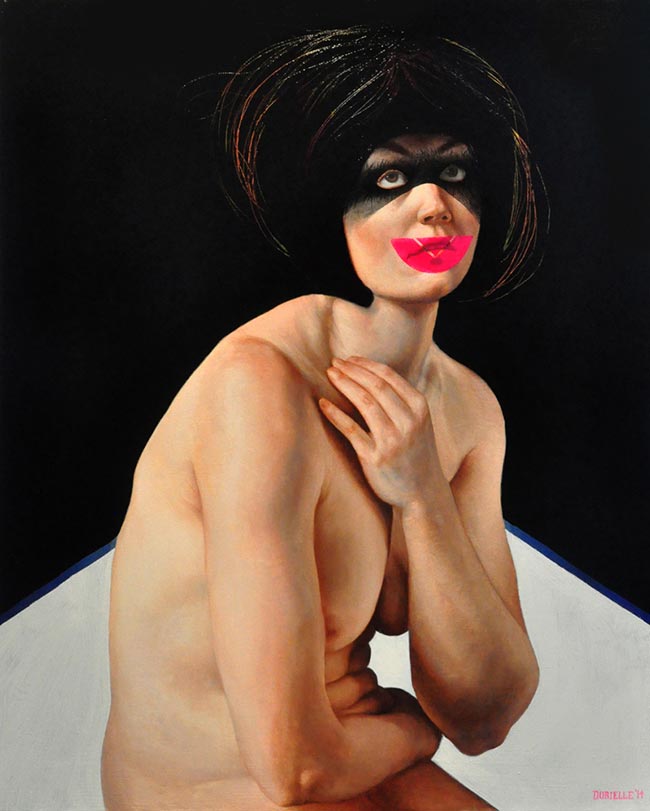

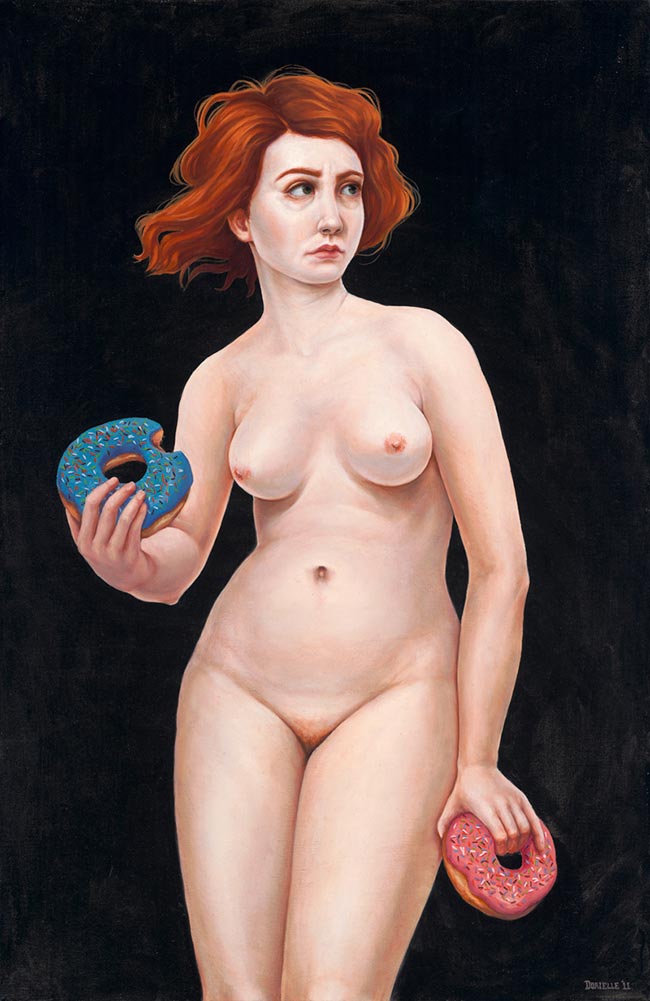

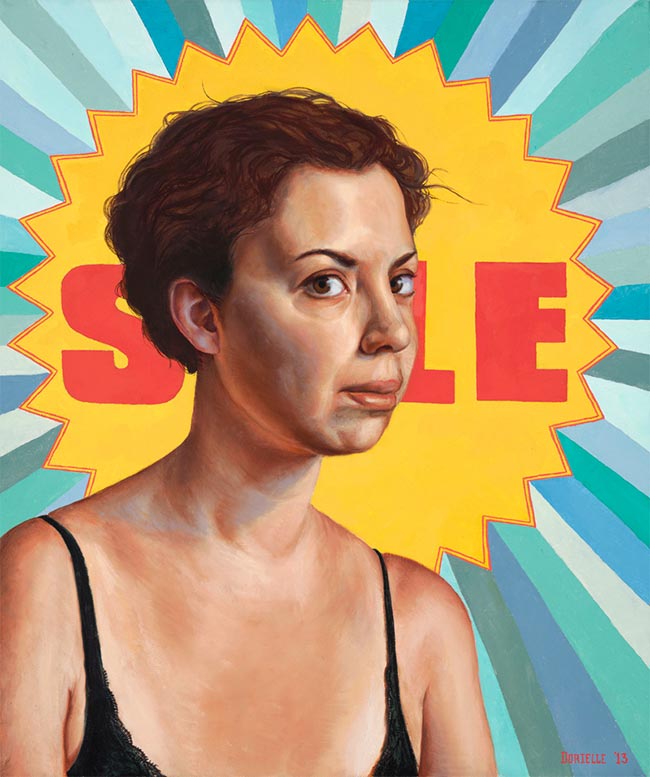

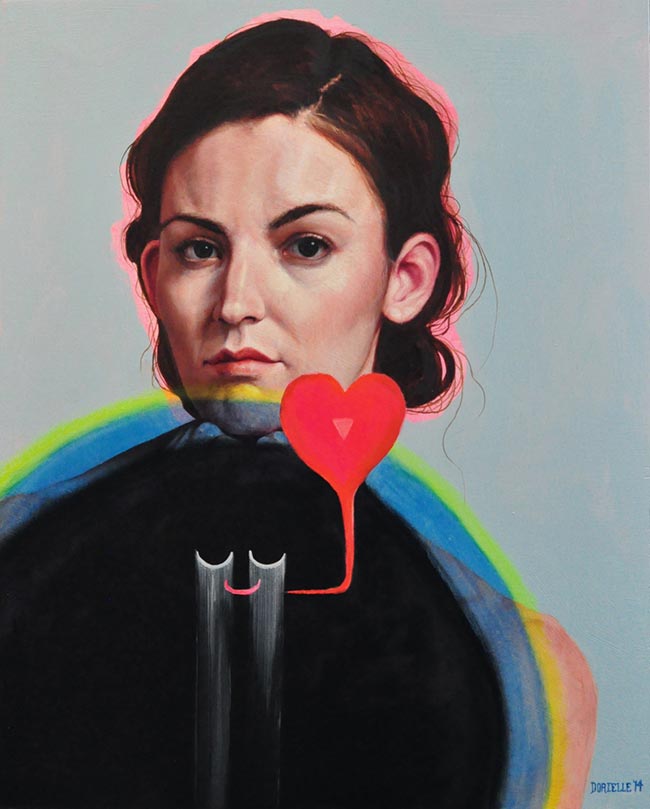

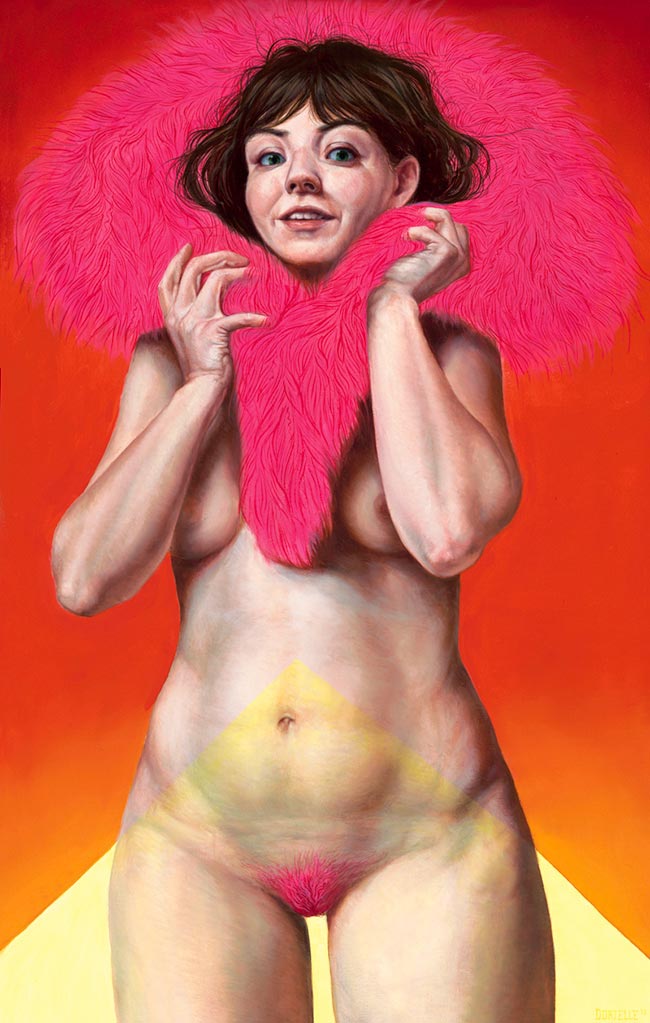

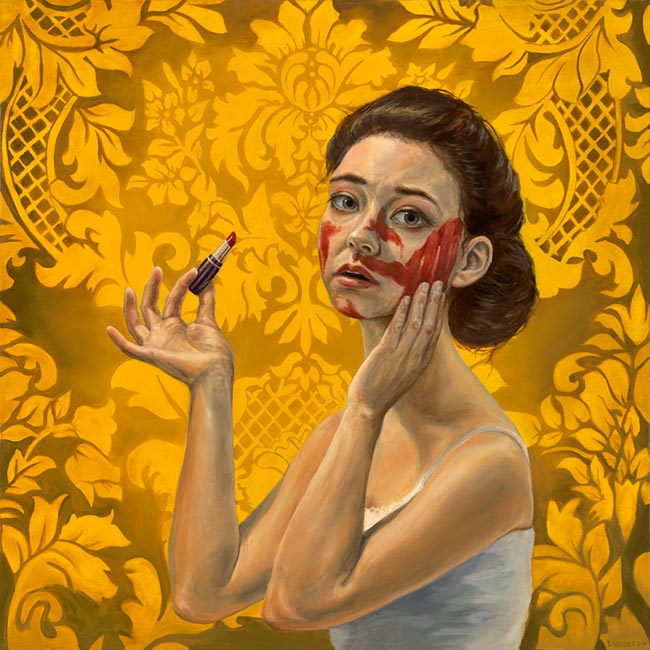

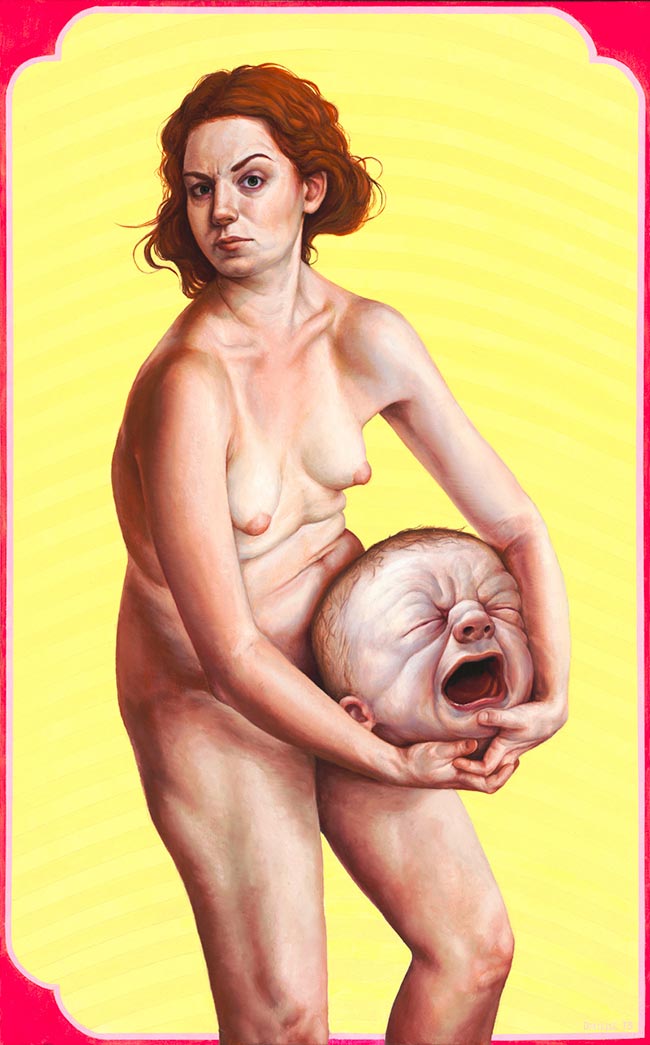

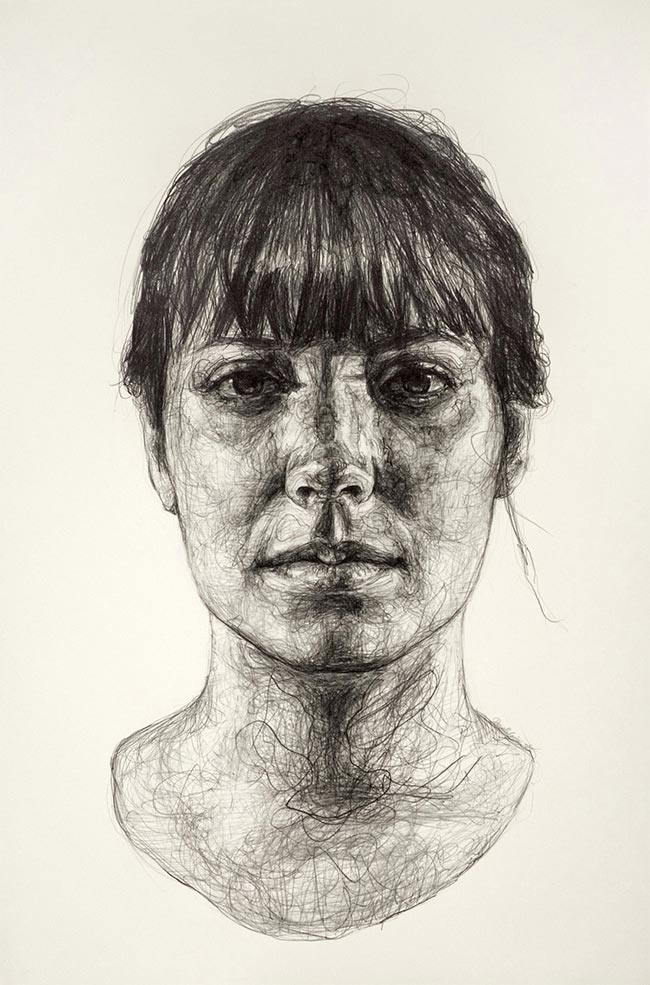

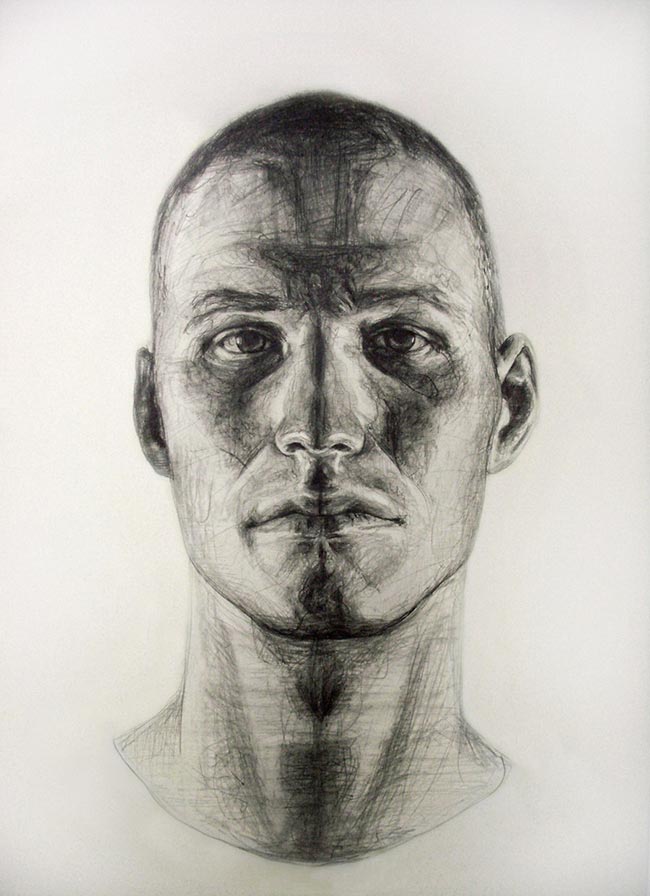

Dorielle Caimi paints from a place of unadulterated honesty and her paintings serve as the memoir of her journey through contemporary life as a woman. They are visual contemplations of her everyday experiences, inner struggles and growth. Predominantly focusing on the female figure, Caimi’s nude depictions avoid sexualization and instead present windows into the complex psychological personas of her protagonists. Intent on not date stamping her work, Dorielle skillfully combines her inspirations from epochs within classical art with 21st century influences, creating a timelessness in her images and also the implication that her thoughts and concerns are not limited to herself, nor to this era, but extend to past generations, through to our own and beyond.

Dorielle Caimi was born in Alexandria, VA, USA in 1985, raised in New Mexico, and currently lives and works in Oakand, CA. She completed a BFA (Summa Cum Laude) in Painting from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, WA in 2010 and a Master Class in Painting at the Art Students League of Denver, CO. in 2013. Her work has been exhibited internationally and featured in many high profile publications, including Hi-Fructose and Juxtapoz.

WOW x WOW caught up with Dorielle in order to ask her a few questions. Read on to find out more about this remarkable young artist and her extraordinary work.

Hi Dorielle, thanks for taking some time away from painting to have a chat. Can you start off by telling us a little about your background and what lead you down the path of choosing a career in the arts?

Well, I once went to a Chinese restaurant and got a fortune cookie that had three fortunes in it and they all said, “You have a deep appreciation for the arts.” So I decided that that settled it. Just kidding. Not about the fortune cookie; that actually did happen. But, like most of my creative peers, I was always drawing as a kid. I loved art class. I also loved writing and music, but my favorite genre was always the visual arts. My family is extremely artistic on both sides. My dad was always coaching me in my work, pushing me to develop my skills and to be original with my content and concepts. I initially resisted a career path of visual arts because there were lots of other fields in which I was interested. But I decided to pursue art because it was the only thing I kept coming back to and that opened its doors to me. My piano teacher once told me that I could do anything I wanted, but do one thing at a time. I think she said this because it’s important to allow yourself to completely become immersed in a field in order to truly understand it and realize its potential.

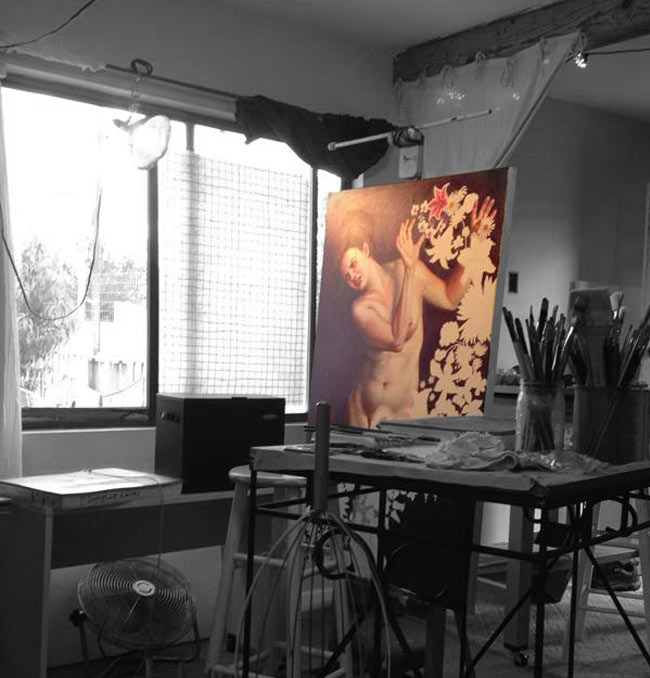

What does your studio look like?

I currently have two studios: one in Oakland, CA and one in Albuquerque, NM (where I grew up). I travel back and forth between the two throughout the year. My Oakland studio is a 250 sq. foot renovated storage unit. We talked the landlord into letting us transform the space into a studio and put windows, skylights, and drywall in it. It’s very nice, but because I’m a very sensitive person I travel home to NM to get away from the noise and hustle of the city. My studio in New Mexico is in my childhood home. It’s a renovated garage with windows, built-in shelves, a separate entrance and it is so quiet. We have a chicken coop right outside so I usually have chickens looking in on me while I work. As far as items in the studio, I’ve found that I really just need the basics: a painting table, my paints, brushes, pallet knives, solvents, and pallet. I have a desk in each space. I wish I had a piano in both spaces, but for now, my piano exists in Oakland. Playing piano helps me to break away from the visual stuff that I do.

Talk to us about your creative process and what occurs before you pick up a paintbrush?

Typically, my process starts with just paying attention to the random visual thoughts that pop up in my head. This happens all the time, but more so when I’m actively painting every day. I like to say that my thoughts are auditioning to become paintings. Most of them are duds, but the good ones I write down in my phone as soon as I think of them: size of canvas, colors, composition, possible names, etc. They usually come into my head with a strong emotional component; the stronger the emotional element, the more I pay attention to them. I usually try not to analyze the images until I’m about 75% done with the painting. I don’t talk to people about the ideas I get because I don’t want opinions and outside input while the work is in its gestation phase. I like for the work to come from that bizarre and pure place of inception. Once the painting is underway on the canvas, then I’m usually open to people seeing and talking about the work.

Your work illuminates and challenges the stigmas and struggles which our society has created for its women. What thoughts and feelings do you hope your art produces in both men and women?

There are a lot of struggles that women face as females in modern culture. But my work doesn’t so much come from direct concern I have for the female race as it does from my own personal struggle and experiences. Really, I can only illuminate stuff that I’m going through; if other people resonate with it, then great. I try to keep clear from any agenda in my work because I like to stay fresh with the changing tides of my experiences, inner conflicts, and growth. Although I have no control over how the world sees my work, I hope that it allows its viewers to feel what I feel when I create the work: namely empathy and understanding of each other and of ourselves.

What have you found to be the main differences between the way male and female audiences react to your work?

Women tend to respond to the work in an empathetic way. I get a lot of emails from women saying that my work provoked an emotional response in them, and that they feel understood by the work. That is the best response I could hope for. But I also have a lot of great conversations with men who really understand and cherish the feminine psyche that innately comes forth in my work. What’s surprising is that my male audiences usually find that they are able to look past the nudity and into the complexity of the women I depict. And then there are some men who completely empathize with my figures personally. This is one of the most inspiring responses I get because I see that men and women share many of the same emotions and experiences. It indicates to me that many of my own struggles are universal and are not partial or exclusive to the female side of humanity.

As a feminist, is there any particular wave or type of feminism that you most identify with? Could you talk about any feminist works that have had a big impact on your views?

I’ve recently broken away from using the term Feminist. I’ve been a die-hard third-wave feminist for 15 years. I know all the issues and history of feminism, but I found that the more I entrenched myself into the –ism of femininity, the more my work began to polarize itself from the inside out. The word has a very exclusive connotation. I believe everything that feminism stands for, but I think the word is too dated, loaded and one-sided, and frankly I think there’s a reason why many women are tender, tired, and defensive with regards to this term: it belongs to an era of yesteryear. Furthermore, with the rise of different forms of gender: bisexual, transsexual, homosexual, etc., I find that a more relevant term is Gender Equality.

As far as feminist works that have impacted my views, none really come to mind.

Shining a light on the psyche of your protagonists is a key factor in allowing you to get your message across. Can you talk to us about this side of your work and what you find to be the main challenges when it comes to portraying the inner self?

Creating art becomes the most challenging when I allow myself to become indifferent. It is almost impossible to define a sedated psyche. My biggest fear is that I will fall into the motions of life and run out of material. As an artist, it is my job to stay constantly aware of my thoughts and surroundings, to think critically, and practice being in the moment. I think that’s why being an artist is so maddening and rewarding at the same time.

I have to create a lot of protective psychological constructs so that I can continue to create without going nuts. I have a daily routine that includes exercise, meal breaks, and it’s segmented into computer work and painting work. When I’m done painting for the day, I don’t take the painting around with me in my head, and I definitely don’t look at it if I’m not prepared to paint. Once I enter my studio all the ominous inner voices are not welcome (sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t). And most importantly, I tell myself that I’m just doing my job and that, as much as I feel actualized and energized by my work, so too can I easily fall into the despair that comes with allowing myself to become to high or self-congratulatory. It’s a delicate balancing act, but I intend on doing this for the rest of my life, so I try not to let myself to get caught up in the preciousness and innate protectiveness that comes with laying bare my psyche.

Your clever use of symbolism aids in the construction of your narratives. Do you find yourself drawing from a universal bank of symbols or do you prefer to invent your own?

Both. As much as I prefer to focus on my relationship with my work, I can’t exist in a vacuum. It is important to consider my audience to a degree. But because I’ve been raised on this planet, most of the things that I think of painting are things that most people know about anyway, so I just try to trust that the symbols that really resonate with me might also do the same with others.

The subject matter for your art is heavy and challenging and yet you deliver it to us with a wry smile. How do you approach the humour in your art and do you ever find it difficult to get the balance right?

In my opinion, some of the best humor is derived from heavy situations: like when Chris Rock talks about racial tension, or when Jon Stewart can make people laugh about abysmal current events. They make people laugh but they also educate people, as well.

I won class clown for my school yearbook, and had always wanted to be a comedian. I can get pretty intense with foreign accents. But on the flip side, I am perpetually dark and complicated, as we all are to varying degrees. I was a very intense child with a lot of frustrated and, for lack of a better word, ‘hyper’ energy. I think that I developed a sense of humor as a way to make light of the heavy stressors in my life. I was always the comic relief in my family when there was tension. This year I’ve been dealing with a back injury that came from painting. I was bed ridden for 4 months. My morale had never been lower, but there were times when I just had to chuckle at my predicament and roll my eyes at the universe and that always made me feel better. That’s the only way I can describe where the humor in my art comes from. I love the paradoxical duality that comes from work that addresses both the heavy and the light simultaneously.

Through your work you doff your cap to various artists within the history of painting, but all the while creating imagery which is very much rooted in the 21st century. Can you discuss your relationship with art history and whether you feel it is a fundamental requirement of every artist to have a knowledge and understanding of what has gone before them?

I think that it is incredibly important to know what artists have done before us. There is just so much to pull from, why wouldn’t you want that wealth of knowledge in your toolbox? But then again, maybe an artist would be better off without the influence of art history. It’s hard to say. I’ve got the knowledge of art history in my arsenal, so I figure might as well use it. Personally, I love High Renaissance painting. I also love the Pre-Raphaelites and the Impressionists. And eventually, through a lot of schooling, I acquired a deep appreciation for modern and contemporary art. But I always (and still do) feel torn between classical and contemporary art. As far as I can tell, there is a war going on between the two. And I think that’s too bad because putting them together makes a whole new soup that I find very satiating.

Why do you think that painting is still managing to stay relevant, irrespective of many critics and academicians proclaiming its death over the years?

Because as long as people are painting, it will continue to be relevant. Everyone is always trying to proclaim that something is dead. I try not to think that anything is ever dead because you never know what you might need to pull from in your career and/or life. I think it is very dangerous and presumptuous to claim that something is dead. Just drop it, and go create something.

What’s next for Dorielle Caimi?

I am planning for two solo shows next year (2016): one at Gusford Gallery in Los Angeles and one for Hiestand Gallery at Miami University in Oxford Ohio. As far as my work goes, I’m not sure what will make its way out of the woodwork. But I have a lot of ideas stored in my phone so it’s just a matter of bringing them to the canvas and allowing myself the freedom to listen, stay present, and trust myself to do as I please.