Adrian Cox is deeply passionate about art and it’s history. It is through his particular passion for figurative painting that the thematic seeds for his current work were sown. Adrian has placed his focus on disrupting the ways we interpret the man-made catagories which we all resort to using when comtemplating the natural world and our place in it. During the analytic process, he started breaking down and blurring the boundaries between humankind and our surrounding environment. By way of this, Cox was inspired to create his Border Creatures and their home, the Borderlands. These creatures may appear grotesque, however we need to overcome our instinctive repulsion and look deeper into what these vulnerable beings have to teach us about ourselves, our egos, our concepts of ugliness and beauty, and most of all, about our interactions with our environment and each other.

Adrian Cox was born in 1988 in Georgia and is currently living and working in St. Louis, Missouri. He received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 2010, from the University of Georgia. In 2012 Adrian earned his Master of Fine Arts degree from Washington University in Saint Louis, and was awarded the Desert Space Foundation Award upon graduation.

WOW x WOW were curious to find out more about the Borderlands and their inhabitants, so naturally jumped at the chance to speak to Adrian in depth about his creations. Find out what he had to say in this insightful and engaging interview.

Hi Adrian, thanks for making the time to have this chat with us, we really appreciate it. To get the ball rolling, if you could tell us a little about yourself, touching on where you currently stay and what you like about the area, any formal training you may have benefited from, etc.?

I’m a Southerner born and raised, but I’ve somehow found myself living and working in Saint Louis, Missouri for the past five years. I never would have pictured myself as a Midwestern painter, but Saint Louis is really a great city to be an emerging artist in. Space is absurdly cheap, which means that I can work in a large studio while moonlighting as a curator at an artist-run space. These opportunities would certainly exist in other cities, but they’d require a bit more of a monetary investment.

I’m originally from Georgia, where I received my Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Georgia in 2010. UGA’s undergraduate painting program had a strong emphasis on expressive figurative techniques while I was studying there, which definitely sparked my interest in working through representational practices in an unconventional way. I moved to Missouri for my graduate studies at Washington University in Saint Louis, which was an amazing experience. I found myself thrown into a highly conceptual program geared to interdisciplinary practices, which forced me to think and speak about my work in a completely new way. There were a number of artists in the program at the same time who were deeply committed to the practice of painting, several of whom worked figuratively. The long nights that I spent debating philosophies of painting with them over cans of cheap beer were formative in the best way possible. After graduating, I stayed in town to teach, and am currently working as an adjunct lecturer at Washington University in Saint Louis. It’s fantastic to be able to teach aspiring artists for a living, and I’ve become as passionate about my pedagogical work as I am about my studio practice.

Your art centres on what you refer to as your ‘Border Creatures’. Can you please give us some background on their development and expand on the concepts they encapsulate?

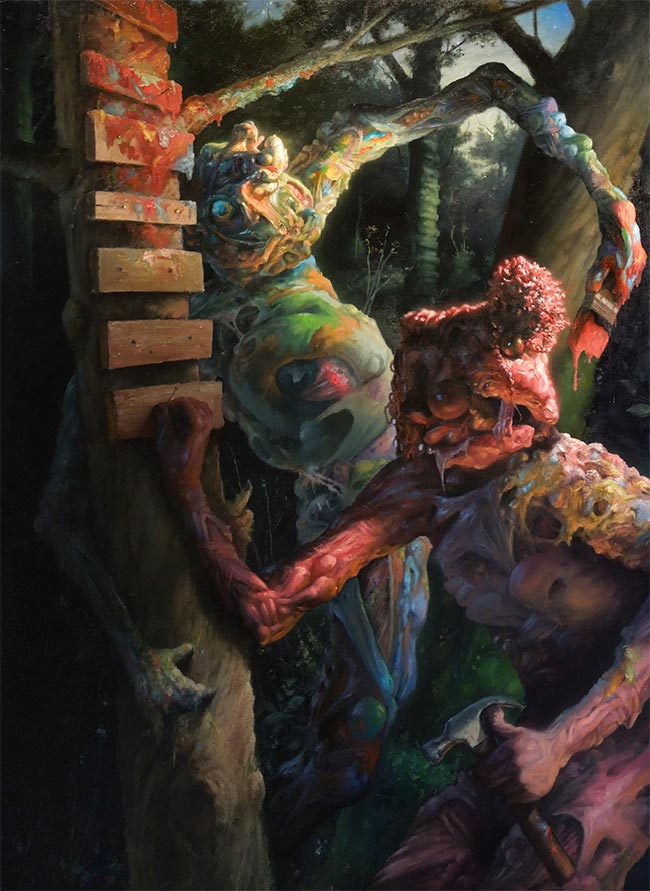

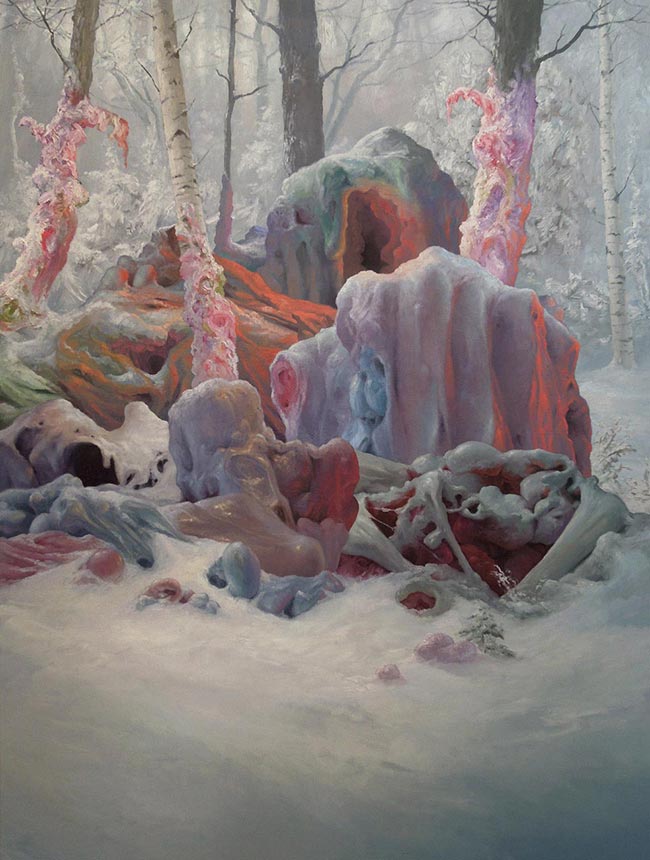

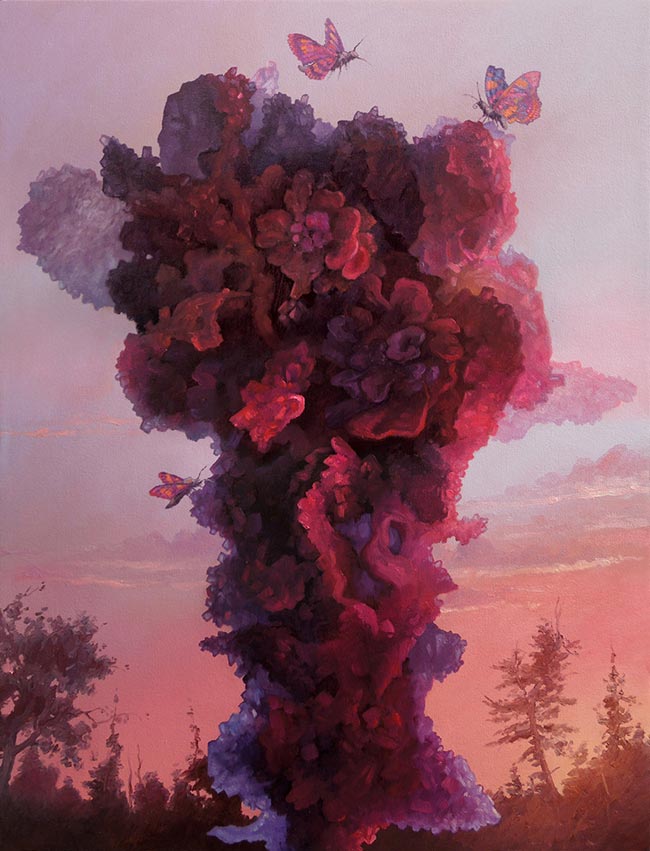

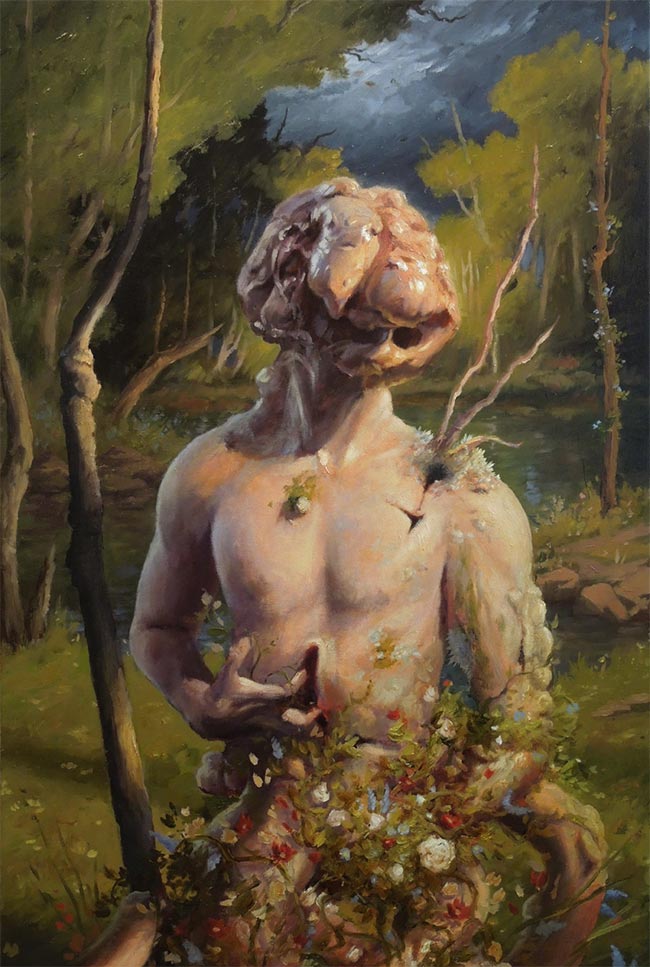

The Border Creatures actually evolved from more clearly human figures. My first experiments with painting these monstrous characters and their forest home came from an interest in disrupting the way that we usually think about the categories of man and nature. I believe these to be culturally defined concepts and not innate truths. Ideologically, I’m not sure it’s constructive, or even possible, to promote the idea of some kind of pure and primal natural world. However, I think it’s equally impossible to disregard the importance of the relationship between humans and their environment. My work speaks to these issues through the genres of painting that have historically helped defined them: portraiture and landscape. The elevation of cultured man in traditional portraiture is obliterated in my work through anatomical mutations that reference natural growth as much as human viscera. Likewise, the idea of a pure natural world is confused by the artificial staging of these scenes, and the symbiotic relationship that I depict between these monstrous figures and their environments. The Border Creatures are hybrid creations, and sit at the intersection of plant, animal, human, and mineral. They contain elements of the landscape they inhabit, and the landscape in turn begins to reference them.

Over time, this more abstract interest in the broader questions about nature, beauty, and monstrosity has evolved into something more whimsical, and I’ve formed an ongoing narrative with recurring characters that connects the paintings. The figures that I depict aren’t anonymous Border Creatures to me, but have become Romantic anti-heroes of a sort. My recent paintings are populated by whistlers, artists, singers, lovers, stargazers, gardeners, mystics, and wanderers. Likewise, I’ve started to elaborate on the role of the Border Creatures as caretakers of their strange wilderness home, the Borderlands.

What sort of research do you do before you pick up your paintbrush. If you could please tell us a little about your process?

The process of generating the fantastical anatomy in my work is fairly involved. I sculpt models of the Border Creatures before creating a painting, which are made out of anything and everything I can buy cheaply at an art supply store or a thrift shop. Some of the materials that have found their way into the sculptures are fake fruit and flowers, rags, wax, socks, plasticine, acrylic paint, gel mediums, joint compound, and fluorescent spray-paint. For my most recent paintings, I’ve been performing some grade-school alchemy by growing sugar crystals on the sculptures. This idea came to me after reading J.G. Ballard‘s description of a crystallized crocodile in his 1966 science-fiction novel The Crystal World. I sometimes use a single photograph of one of these sculptures to create a figure, but more often, I end up piecing together fragments of different models into a Frankenstein collage.

I’m also always digging through art history textbooks, which often trickles down into the finished works. A number of the more narrative scenes incorporate poses that are direct quotes from other paintings. For example, Amniotic Paradise began with sketches made from Caravaggio‘s The Entombment of Christ, and New Skin is a quote of Michelangelo‘s depiction of Saint Bartholomew in The Last Judgement. Even when I’m not directly referencing a single work, I like to contextualize what I’m doing within the history of painting.

Vulnerability is a theme you explore within your work and you seem to encourage feelings of empathy in your audience. What kind of reactions are you aiming to elicit from the viewers of your art, on an emotional level?

I think it’s much more interesting if someone experiences conflicting emotions toward a work of art than any single sentiment. I always strive to achieve a level of pathos in the figures without compromising qualities that might also be unsettling or even frightening. There’s a comic absurdity in some of the works that I think makes the characters more relatable. It’s hard to be terrified by a creature that has a bird or butterflies perched on its head, or one that’s wearing a garland of flowers. With the Grotesque, there’s also a level of the unknown and the unfamiliar, which I’m deeply interested in. When new creatures and landscapes find their way into my work, I like to think of them as recent discoveries from some previously unknown corner of the Borderlands. Thinking through the narrative in this way helps me tap into feelings of mystery and wonder.

Thoughts of life and death are all interwoven into the hearts, entrails and dripping flesh of your subject matter. Can you speak to us about how you go about marrying the two? Also, please talk about your own relationship with the concept of death and how that relates to what you choose to paint?

People tend not to enjoy thinking of all the internal processes that make up the fragile, squishy, unpleasant workings of the body. Some of the early Border Creatures made these aspects of embodiment impossible to ignore. The inside-out qualities of these figures speak to the fact that we’re not just purely rational minds working the control panel of a body, but that many of the qualities that we see as essential to identity are intimately tied to how we live in these bodies. To take this further by showing the body as perpetually transforming rings alarm bells for most people; it calls attention to the reality that humans aren’t continuous beings. You aren’t who you were five years ago, and you won’t remain the same once you’re dead. The term human being is a bit of a misnomer in this way, as it implies that identity is a constant. I tend to favor the label human becoming, and take comfort in recognizing that identity is in constant flux. These ideas strongly inform the funerary rituals that I’ve painted in ‘Amniotic Paradise’ and ‘Eschatology’, as both images depict a moment of celebratory transformation and rebirth through the death of a Border Creature.

There is a beauty within the grotesqueness of your creatures. What are your thoughts on aesthetic beauty in art, and in particular, it’s relationship to the painted world you create?

I’m a complete Romantic when it comes to beauty in art. Intellectually, I recognize that beauty is culturally defined, and that my own work relies on Western aesthetic conventions, but my heart still soars when I stand in front of a painting by William Turner. This really presents the impossible goal for me in the studio, to create an image that, even for a moment, creates this standing-on-the-precipice moment of breathtaking beauty. The subject matter of my work makes this all the more important to me. Monstrous forms that are truly ugly can be easily dismissed, whereas grotesque figures that are visually seductive demand to be looked at; there is an invitation to transgress conventional categories of beauty together. This kind of painting involves an implicit disbelief in the inherent attractiveness of certain traditional subjects, and shows that aesthetic pleasure can be found in the unusual space between the Beautiful and the Ugly.

When talking about the environment that your protagonists inhabit, you have stated that it ‘holds conflicting qualities in equilibrium’. Would you care to elaborate on this for us?

The environments in my paintings are mostly invented spaces that heavily reference nineteenth century Romantic landscape painting. This particular moment in the history of painting is interesting to me for its paradoxical focus on direct observational study and melodramatic exaggeration of natural features. It’s almost as if by trying to communicate their fervent belief in a pure and savage wilderness, these artists instead revealed the artificiality of this idea for the first time. My landscapes operate in a similar way, holding the awe-inspiring experience of nature in balance with the realization that this reaction is, at least partially, culturally conditioned. I also try to subtly reveal a certain level of artifice through the organization of these spaces. Foreground, midground, and background are always a little too cleanly structured, as if the landscape is more of a stage set than a wilderness painted from observation. I don’t want the Unnatural to negate the Natural in these landscapes, but for the qualities of each to call the other in to question. Constructing the Borderlands is a bit of a balancing act in this way. The goal is to build conceptual tension rather than tip the scale one way or the other.

Your paintings are beautifully rendered and contain a fantastic amount of detail, yet are filled with painterly brush stokes and an expressive flair. How important is it to you that your artist’s hand is obvious in your work?

I strongly believe that a painting is able to do something for a viewer that a photograph or even a reproduction can never achieve. A painting of a body is so much more than image alone; in the best of paintings, the crust of impasto, the gestural scumble, and the slick translucency of a glaze add up to a viewing experience that is as much of the body as it is about the body. This is what I strive for every time I pick up my brush, and it’s the core of my commitment to the art of painting.

Who or what has been the biggest inspiration to you so far in your professional career?

I can spend a whole day browsing a museum’s painting collection. Whenever I feel the beginnings of studio fatigue, I know that an hour with Max Beckmann or Gustave Courbet will leave me eager to pick up my brushes and get back to work. I always hear people refer to the history of painting as a ‘burden’, but there’s nothing more thrilling to me than tapping into such a rich tradition.

Sometimes nothing can help get a more insightful glimpse into the personality of an artist than a tale from their own life. Would you be willing to recall a story from your past that you feel helped shape your creative mind?

I grew up in a lakeside house in the woods. I had very unconventional hippie parents, and they were always showing me tidbits of survivalist techniques, rattling off the Latin names of different plants in the woods, or talking about respecting Mother Nature. The other kids in my elementary school class probably still remember when I brought a snake that I found to show and tell.

If you could own one piece of art from any of the world’s collections what would it be and why?

Oh boy… that’s a really hard question to answer. I think I’d need a bigger apartment first! If I had to pick, I’d want either Camille Corot‘s ‘A Woman Gathering Faggots at Ville-d’Avray’ or Jules Bastien-Lepage‘s ‘Joan of Arc’. Corot’s work has always felt so tender and intimate to me that whenever I encounter one in a museum, it’s like coming across an old friend. Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc on the other hand is simply one of the most stunning displays of painterly bravado that I’ve ever seen in the depiction of landscape.

What’s next for Adrian Cox?

My studio is filled with blank canvases and models that haven’t yet found their way into paintings. Right now, I’m working on a number of crystallized gardener portraits and a few more landscapes. I’m still trying to surprise myself in my journeys to unexplored corners of the Borderlands!