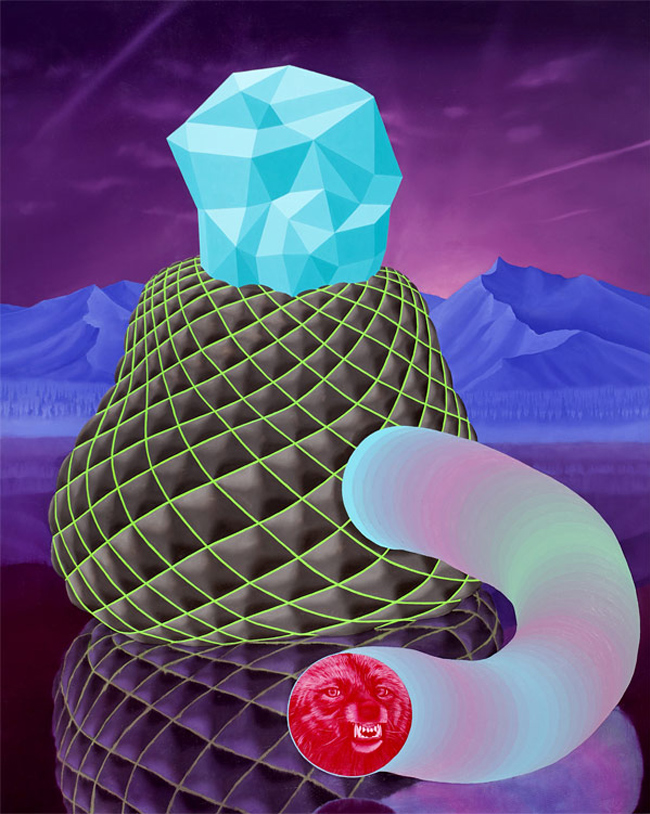

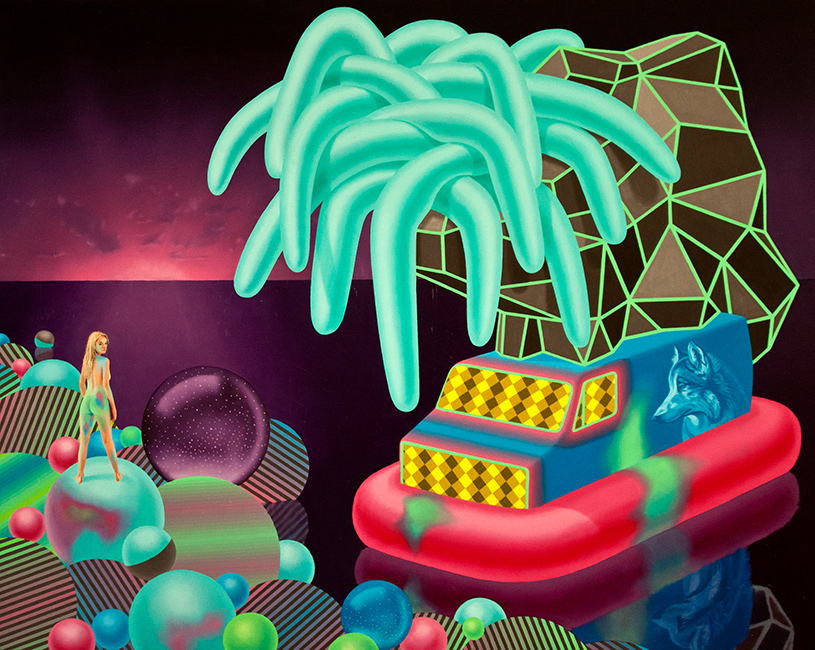

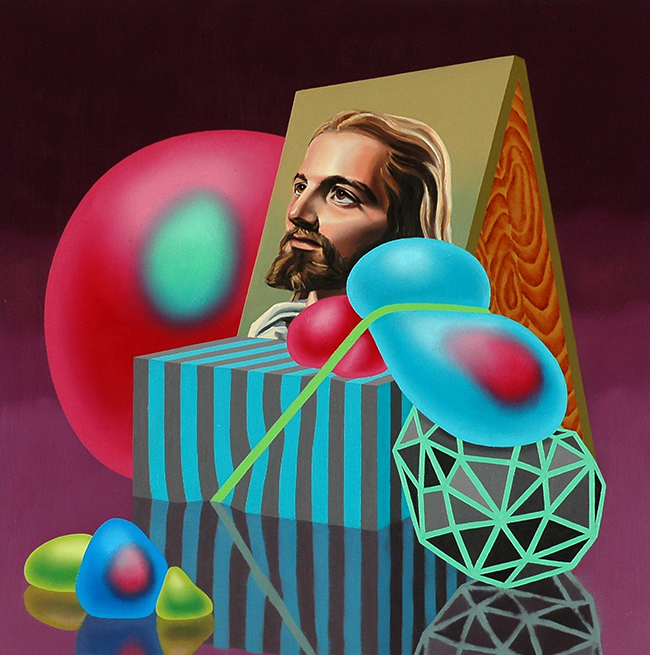

Jaime Brett Treadwell revels in the mystery of creation. He doesn’t need to know all the answers. The ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ related to his artistic practice may or may not reveal themselves to him in time, but he doesn’t mind either way. It’s the enigma surrounding the genesis of creative thought and inspiration that keeps the whole pursuit interesting for Treadwell. This is not to say that Jaime does not make well informed and educated choices during his process, because he most certainly does. Within his most recent panoramas of highly saturated colour and objects of seemingly impossible construction, he questions the relationships between high and low culture; illusion and deception; reality and non reality. Throughout this work, Treadwell effectively re-presents imagery out of context and challenges us to engage with contradiction, in order to find new and relevant meaning.

Jaime is an American artist, who was born and raised in a suburb of Philadelphia. He completed his undergraduate education at the State University of New York at Cortland in 1999, and earned his MFA from the University of Pennsylvania in 2002. His art is exhibited and collected around the world.

WOW x WOW are delighted to be able to bring you all the following interview with Jaime, in which he discusses a host of interesting topics, including important aspects of his working practice and his views on the relevance of painting.

Hi Jaime, thanks for taking the time to talk to us. Before we go any further, can you tell us a little about where you live?

Currently, I live in Philadelphia. I was born and raised in the suburbs of Philly, and also lived out west for a couple years. Eventually, I came back full circle to attend graduate school at UPenn. I decided to stay, buy a house, and set up shop. Over the years, Philadelphia has increasingly become a thriving contemporary art community. It’s affordable, close to NYC, and a great place to make work.

Please give us a brief history of your relationship with art?

Art has always been a part of my life. I knew at a very early age that I would pursue the path of an artist. I use to have ‘art stands’ instead of ‘lemonade stands’ on my parent’s front lawn. I sold one pastel drawing for 4 dollars. Undeterred, I continued to focus on art throughout high school, college and graduate school. Currently, I teach full-time at Delaware County Community College. I have a range of talented students whom are focused and determined to get to the next level. I truly enjoy helping them achieve the skills and knowledge to move forward and reach their goals.

You are just fresh off the back of a stunning solo exhibition at Mirus Gallery in San Francisco, entitled ‘Trick Magic’. Can you give us an insight into the ideas you were exploring when creating this new body of work?

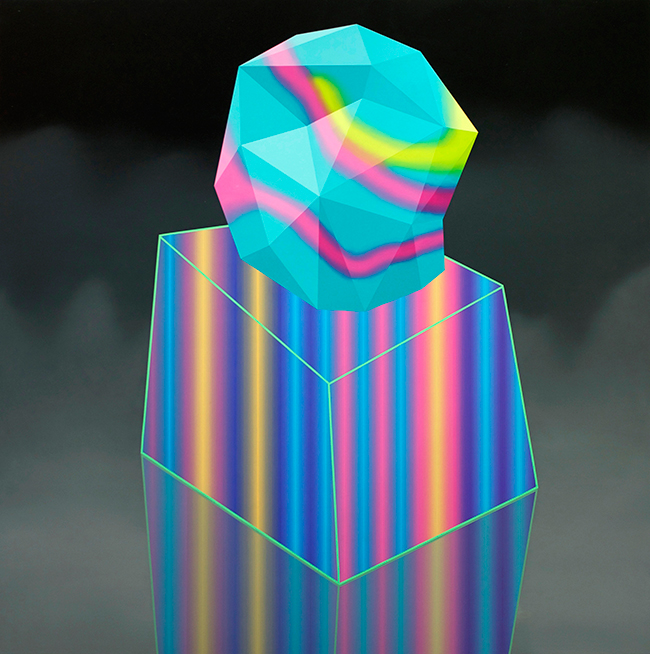

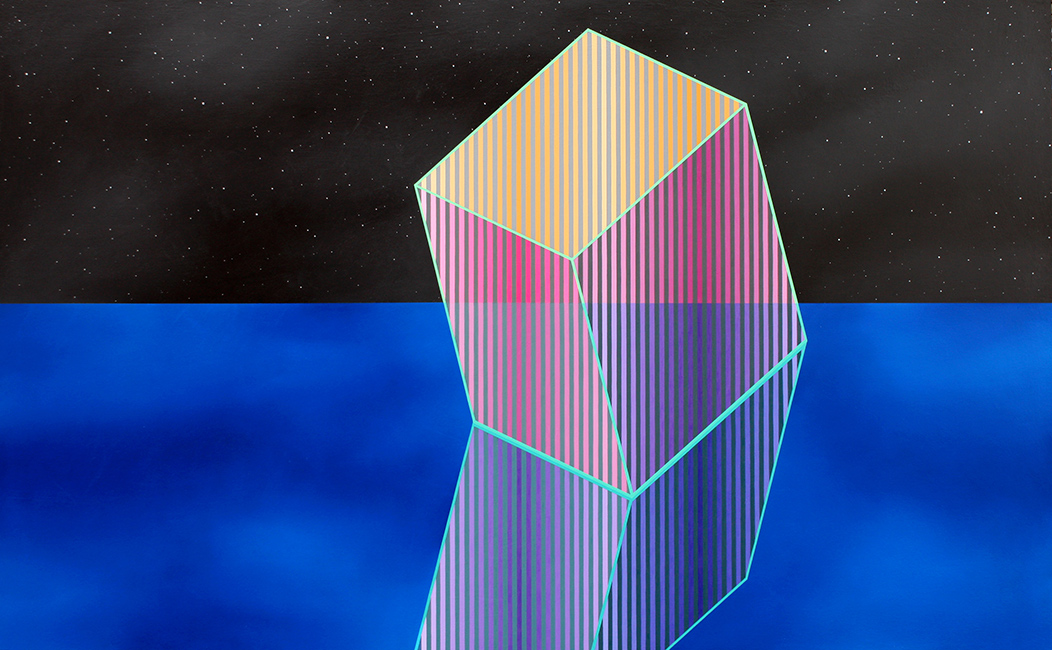

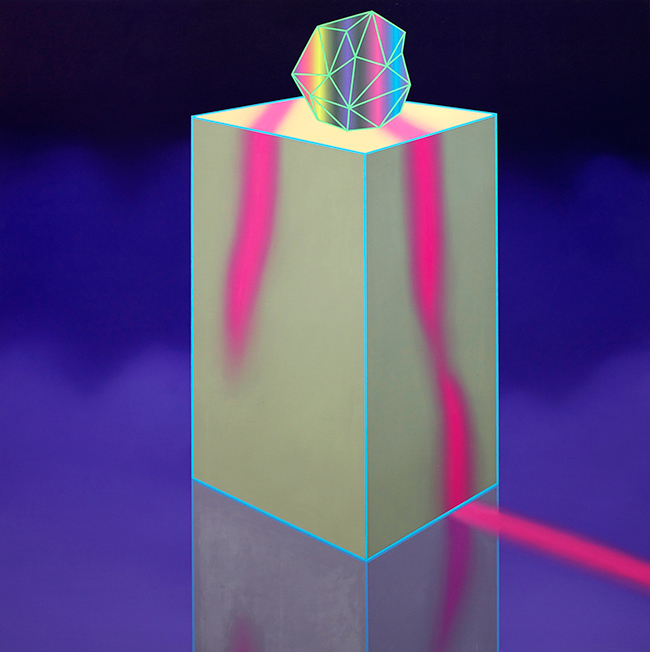

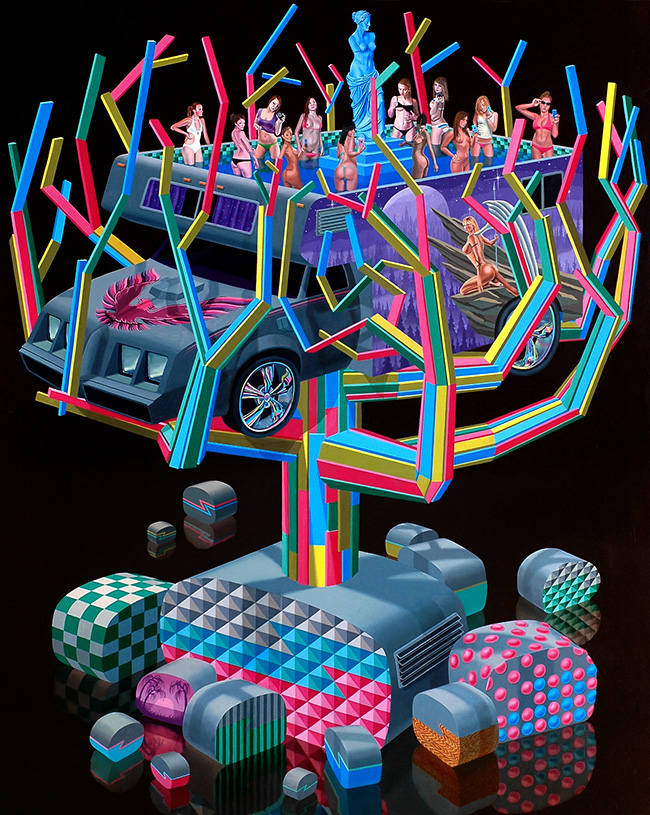

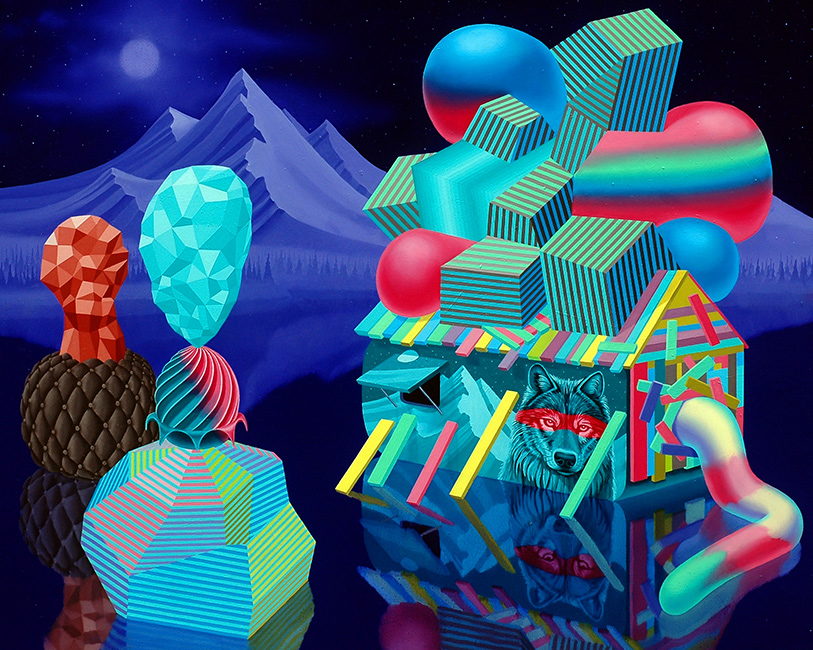

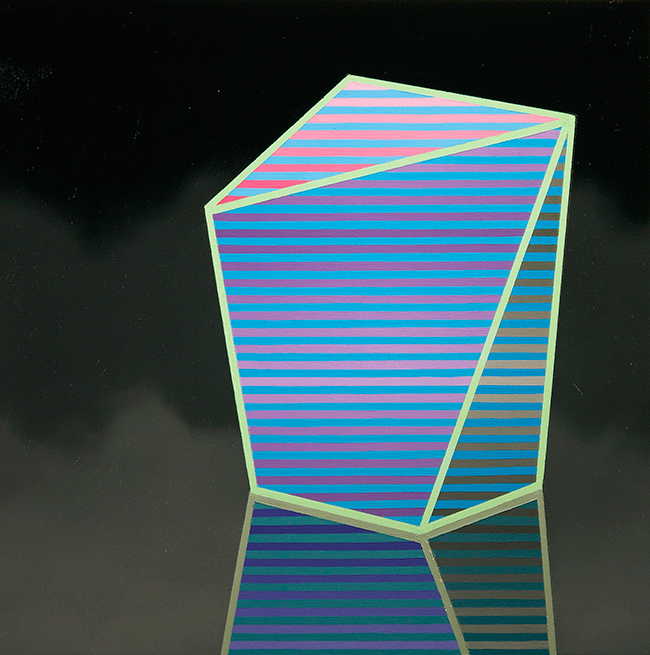

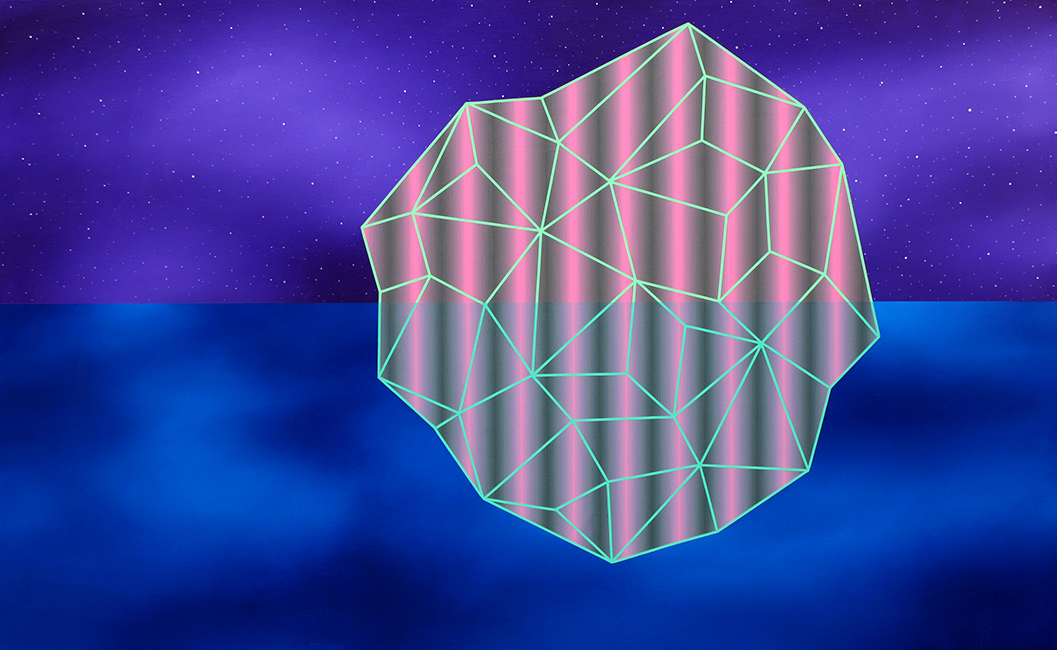

Thank you! I worked on that show for two long years, and I am satisfied with the outcome. Originally, I began each painting by creating images of sculptures that I imagined a self-taught artist living in deep isolation would make. Eventually the paintings took on another identity. I remember staring at 5 or 6 completed paintings and thinking how much the work resembled elements of a magic show such as deception, illusion, ambiguity, drama, smoke and mirrors, humor, etc. I thought the title matched the theme in the paintings and related to ideas I have worked with in the past. Most of my former work fuses high and low imagery, and I think magic shows possess that same relationship. The difference between my new work and older work is that the imagery is not as narrative or literal in the latter. My new work begins to enter into the realm of non-representation, but also fuses elements of reality. I think of my recent paintings as a series of invented, physically impossible forms, existing in a real space. What I liked most about this body of work is that each painting feels plausible, but also possesses an unfamiliar mystery similar to magic. The body of work is still new to me and I will have a better understanding of it in retrospect. However, I don’t like knowing all the answers because that can take the mystery out of making art.

The colour palette you use is bold and arresting. How do you wish the viewers of your work to be affected by your use of colour?

My use of color helps to establish a world of fantasy and fiction. I hope that viewers are able to enter a meditative state for a moment…maybe escape from reality and live in a new strange place. I know that sounds corny, but I have that experience when I look at fantasy art from the 70’s and 80’s, or paintings from French Rococo artist Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée. I disconnect from reality for a moment and enter a place of pure autonomy where child-like imagination takes over. If my use of color can encourage that feeling in others, then I’m satisfied.

There is an obvious high level of technical skill involved in the paintings you create. Whether it is required for the clean, crisp, hard-edged line work or for producing your seamless colour gradients. Did you learn a lot of your technical virtuosity during your own formal training or have you developed these skills through your own trial and error?

I was fortunate to have had an undergraduate art education that placed a focus on strong technical skills. However, I believe that being a teacher is what has refined my technique. I demand excellence from my students with regard to craftsmanship, which forces me to practice what I preach. Also, it’s no mystery that practice makes perfect. The author Malcolm Gladwell said it takes 10,000 hours to master a discipline and I definitely agree with his theory. Not that I am a master, but the craft of painting takes a heck of a long time to learn.

You have previously stated that you like to explore the relationship between high and low culture. Can you please expand on this idea for us and give an example of how you approach it?

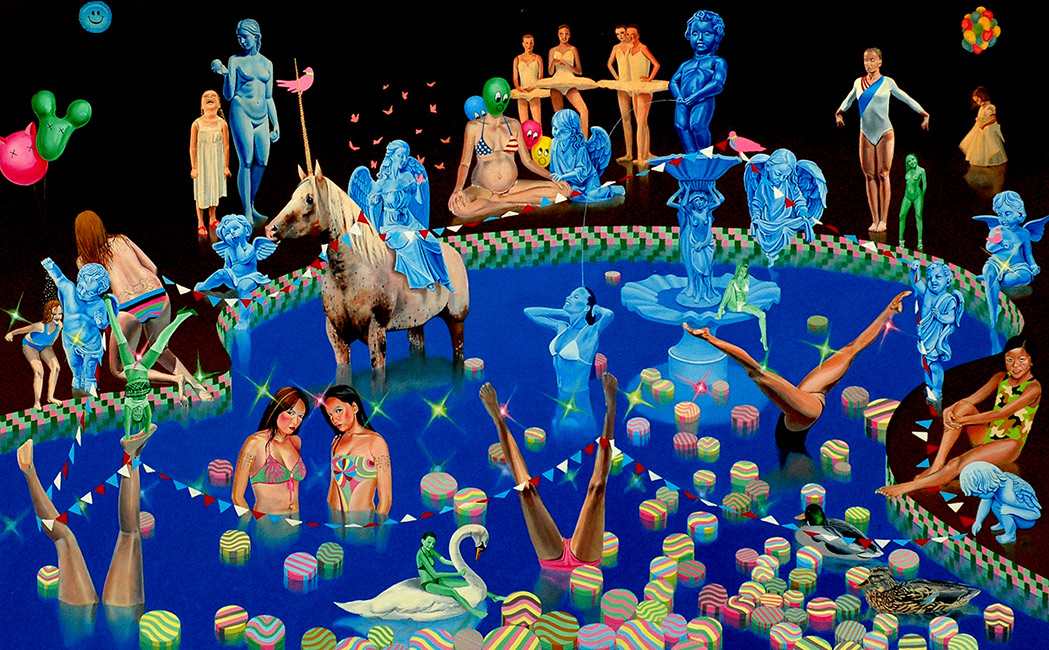

The relationship between high and low culture has somewhat become a common denominator throughout my work. Recently, the high/low correlation is less obvious but still present. My older paintings combine literal examples such as classical Greek sculpture dispersed throughout spring break pool parties; whereas, my current paintings discreetly suggest a high/low reference by mixing street art with Op Art. With each painting, I try to present a balance of disparate elements fused together. I’m pleased when the painting feels like various components shouldn’t be together, but somehow work. The combination of unexpected relationships can result in innovation.

With each new body of work do you find yourself tackling new themes and treading uncharted territory or do you aim to explore the same ideas you’ve addressed in previous work, but from a different angle?

I continue to explore similar themes but I invite new ideas to enter my work all the time. My greatest fear is losing interest or moving backwards. As a result, I try to have some type of new personal discovery when making each painting. At the same time, I’m incorporating elements/ideas from former paintings. To best answer your question, I apply both strategies. I incorporate new elements, but often allow previous concepts to continue forward. The inclusion of new elements does not change the content, but expands the layers of interpretation. I feel my work is most successful when it can be interpreted on many levels.

As a full-time Assistant Professor of Art at Delaware County Community College, do you feel that your interaction with your students has any affect your own work?

Absolutely. I am embarrassingly influenced by anything around me. I often tell people that I would not be making the work I make without teaching the courses I teach. I teach mostly foundation courses such as Drawing, Mechanical Drawing, Color Design, and 3-D Design. These courses provide a wealth of material for me to use in the studio. I am constantly developing new projects for my curriculum, which initiates research in subjects I would not typically explore. Currently, I am researching sculptors that work with casted objects and carved forms for a 3-D Design project. I will spend hours downloading images of sculpture and objects I might use as examples for student projects. However, this is often how I find new ideas to work with in my own studio. I’m also influenced by the project solutions and dialogue generated by my students. For me, teaching is an ongoing project that keeps me in the creative zone and informs my process.

If you could pick the one concept or piece or advice that you would like your students to remember you for teaching them, what would it be?

Talent gets you in the door; work ethic keeps you inside.

What do you feel is the most vital factor for an artist to be open to, with regards to the evolution of their practice?

Don’t give up on an idea because you found that another artist is exploring the same thing. The evolution of your idea will eventually transform into something distinctive to you. I often hear artists say, “I can’t use BLANK, someone has already used BLANK.” There may be a visual crossover in the pathways of two artists, but eventually the pathways continue in different directions. In short, your body of work is completely different than another artist’s body of work. Continue to focus on what interests you and that connective thread will disappear.

Why do you think that painting is still managing to stay relevant, irrespective of many critics and academicians proclaiming it’s death over the years?

I think there is too much history for painting to be irrelevant. Art is about re-presenting something from Duchamp’s urinal, to Warhol’s soup cans, to Koons‘ puppy dogs. As long as you take something out of context and offer new perspectives, regardless of the discipline, you can make art – see Hennessy Youngman’s Art Thoughtz. It’s almost impossible to make a painting without referencing a time period. Whether it’s good or bad is another issue, but most critical dialogue about painting includes rhetoric concerning the history of art, which painting dominates. A great example is one of my favorite painters, John Currin. His most recent work uses hardcore pornographic imagery masked in the style of an academic old master’s painting. The contradiction between pornography and old master painting re-presents pornography as high-art. In my opinion, the relationship between the two makes his paintings relevant and contemporary. History is not the only reason painting stays relevant. In academic fine art departments, the painting program usually possesses the highest enrollment numbers. Materials are inexpensive, accessible, and easy to transport, store, and install. Lastly, the argument alone that painting is dead gives fuel for other critics to keep it alive.

What’s next for Jaime Brett Treadwell?

My alma mater, SUNY Cortland, invited me back to exhibit my work in December 2016. It’s a beautiful space hidden in snowy upstate New York. As a student, I remember going to every exhibition and wondering if I would ever be successful enough to exhibit my work in that gallery. I’m honored to have the opportunity, and I’m looking forward to making a new body of work.