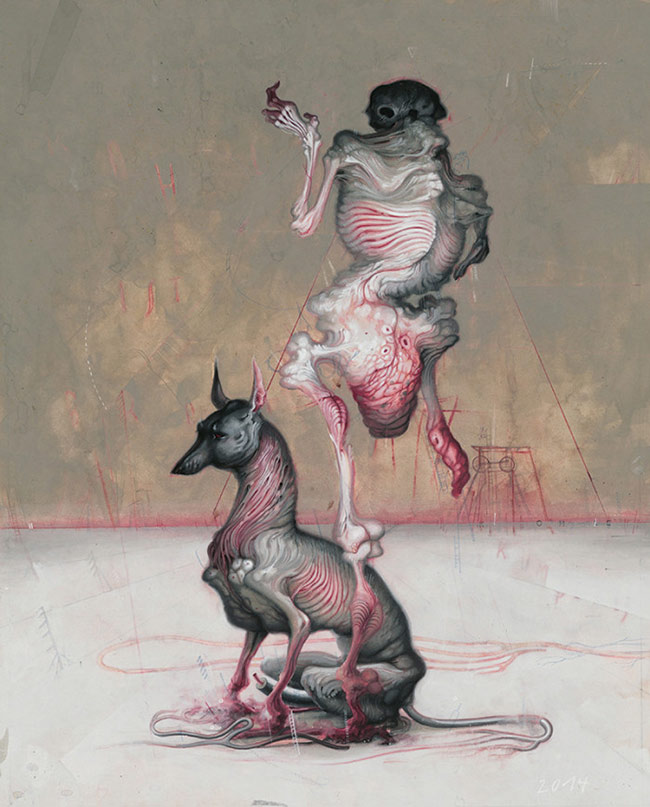

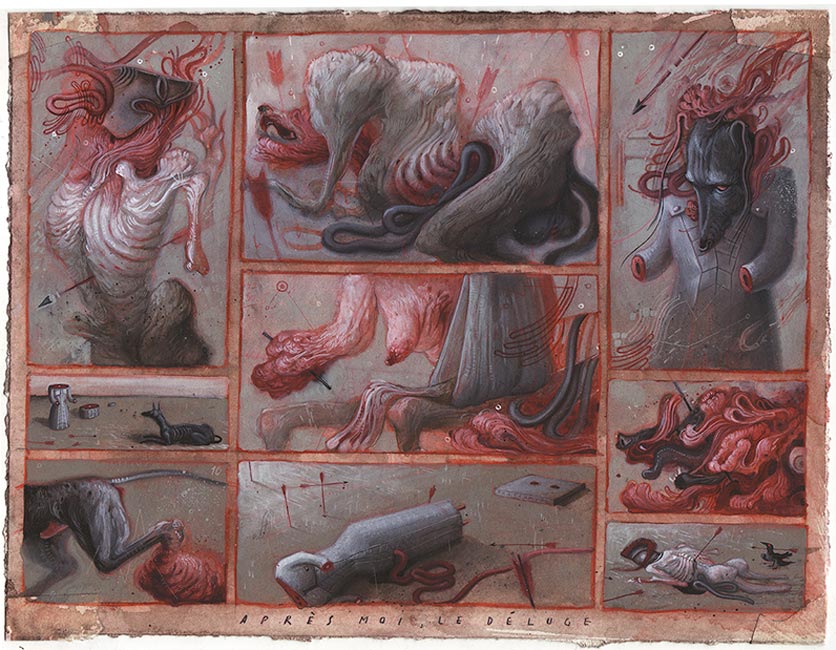

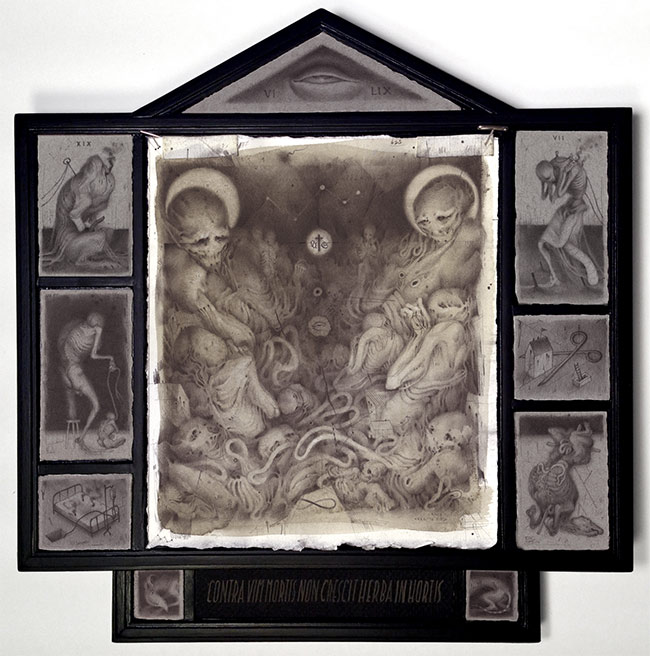

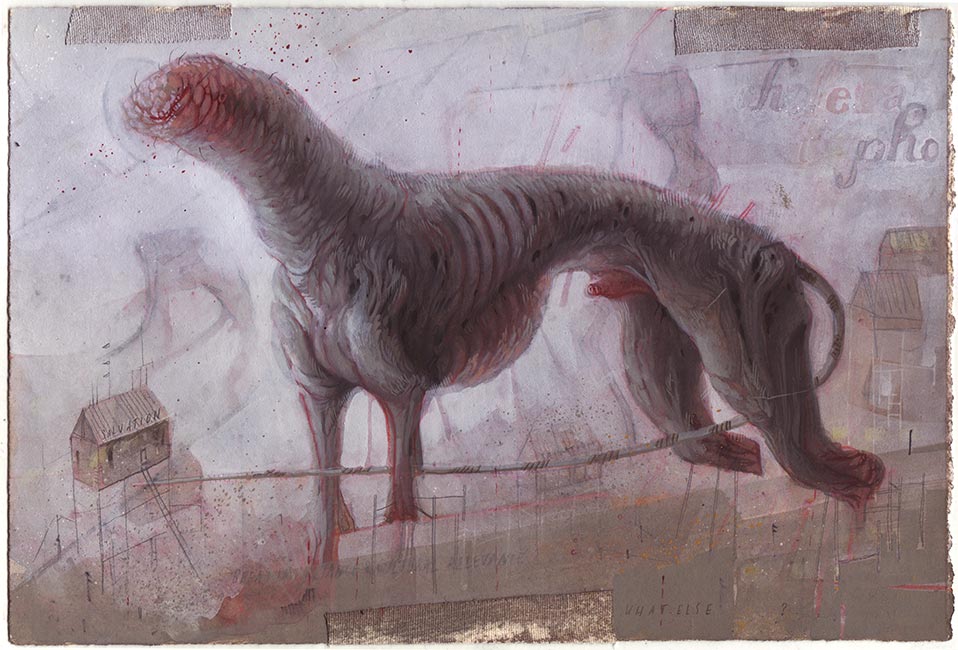

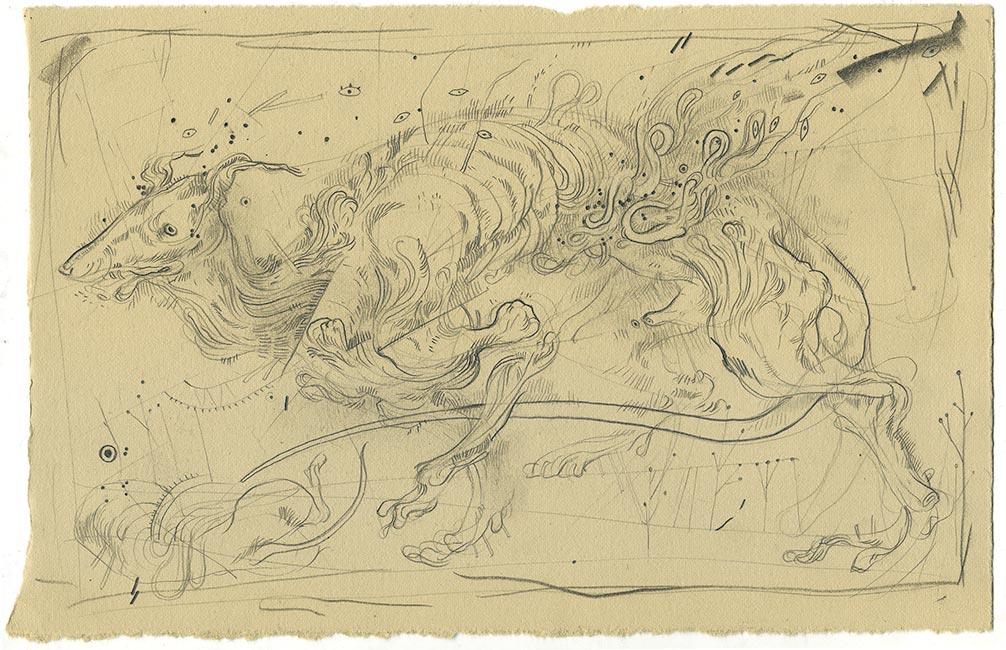

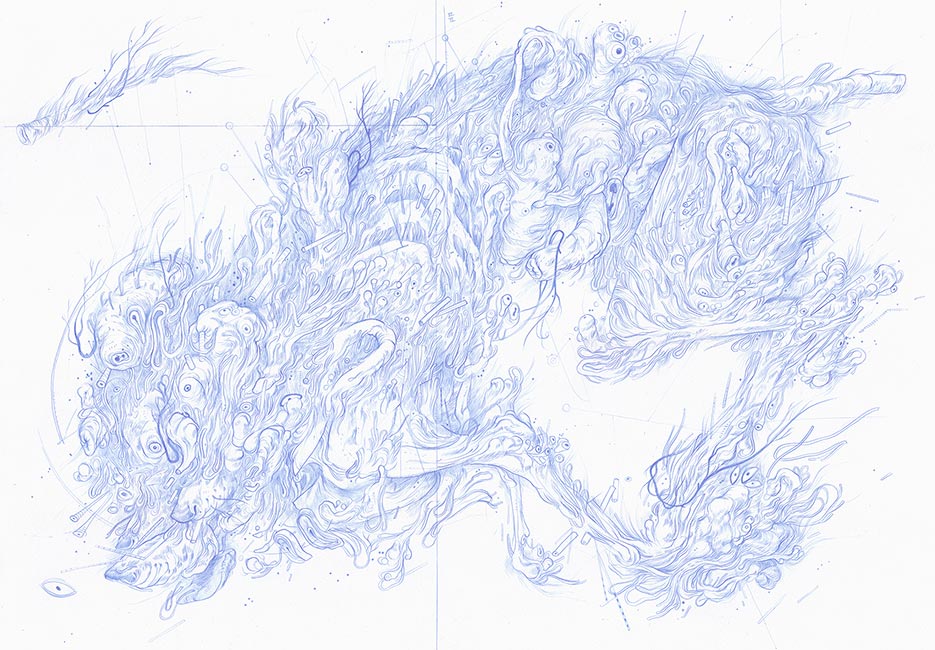

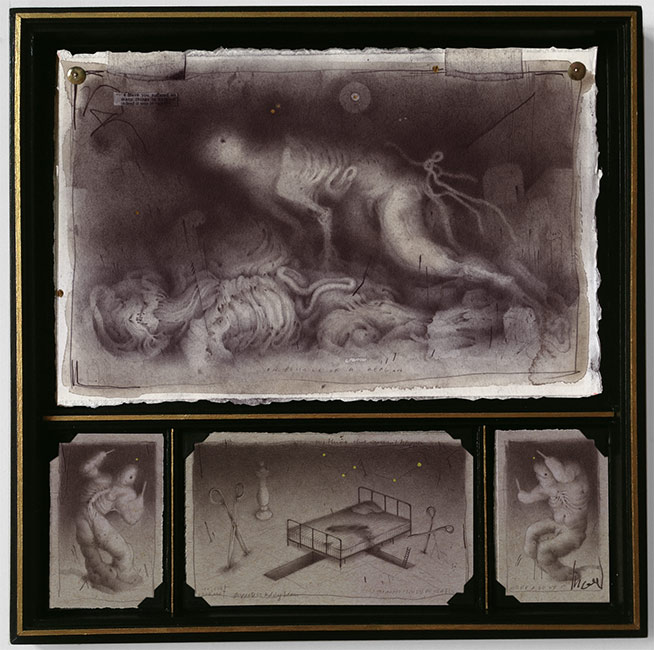

Allison Sommers creates artwork that is both challenging and ambiguous. Simultaneously engaging on both visceral and cerebral levels, Allison’s work incorporates expressionistic interpretations of oddly familiar creatures, which give rise to thoughts and questions about stimulating themes such as, beauty, sexuality, morality and mortality. Sommers appears to take an almost gleeful delight in the notion that interpretation is an amorphous concept, and that the context each individual brings to the table when viewing a work of art, depends greatly on our own personal history, cultural background, personality, etc. By way of creating with a freedom from the concerns of her audience, her gift to us is the ability to derive our own meanings from within her deeply curious and profound imagery, without defined prescription. Something that surely all great art must aspire to.

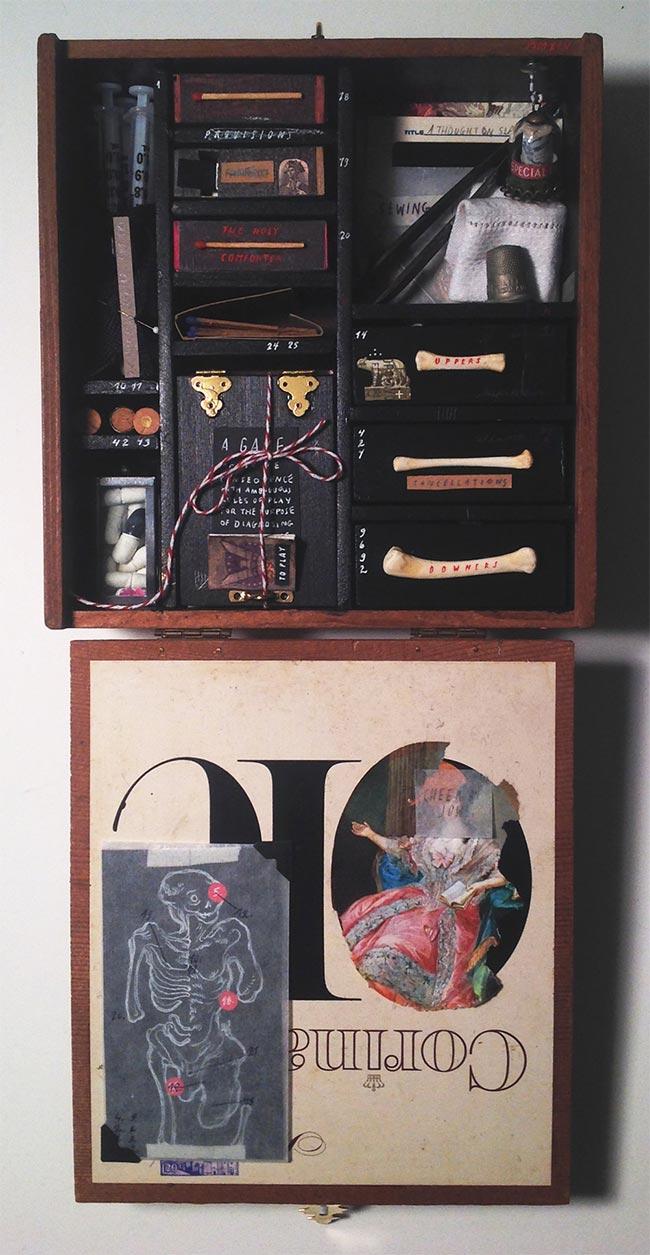

Allison Sommers is an American, currently living and working in Brooklyn, New York. She graduated from the University of Virginia with a BA in History. Allison is a self confessed inveterate magpie, and fills her studio with odds and ends which frequently find their way in to her work or end up as the substrates or enclosures for it. Since becoming a professional artist Sommers has exhibited her art around the world in group shows and has had several solo exhibits in her home country.

WOW x WOW had a recent opportunity to pose Allison some searching questions about her work, inspirations and the evolution of her practice. Read her candid responses in the interview below.

Hey Allison! Firstly, thanks for taking the time to join us for a chat, it’s most appreciated. On your website you refer to yourself as an ‘art worker’. Can you please expand on this term for us and talk a little about your working philosophy?

I don’t have a problem with the term ‘artist’, but, for me, something about ‘worker’ captures (along with an obvious political undertone) a little more of the action of being an artist– that it’s a lot more elbow grease and a lot less muse-worship than I think ‘artist’ conjures sometimes. Studio as workshop (as mess, as sweat, as something that isn’t rarefied) resonates with me, as does the concept of art itself being more of a verb.

How political do you feel you are as an artist?

I’m working hard to be more political in the work itself. I don’t necessarily make overtly political work, not in a 1:1 content sense, although I do try to address gender fluidity and personhood in my current body of work. As an artist, an Art-Person, I consider myself to be quite political, however. It’s impossible to be an artist and not be, the mere act of calling oneself ‘artist’ is a political act.

You have previously talked about the ‘impossibility of actually communicating anything to someone’. Can you elaborate on this concept for us, and in particular how it relates to your art and the decisions you make as a result?

I mean to make reference to the death of the author, in that a viewer’s interpretation of a particular artwork and the artist’s intentions regarding said work must necessarily be separate. Whether we know that we do or not, we look at art with a lot more nuance and complexity than just ‘x symbol carries y meaning universally’, and to try to foist meaning onto the viewer is at best heavy-handed, if not entirely futile. (Insert discussion about academic painting and its Ivory-Tower stronghold on ‘meaning’ here.) I can’t make you see what I mean with a painting, not really, because not only are you not me, with my specific context, even the act of making itself is so different than viewing a painting that the message gets garbled, blurred, or lost altogether. The painting is yours to interpret. I can’t do it for you.

I love to play with this – I sometimes employ symbols that I absolutely do not ‘mean’, just to muck up the exegesis a little more. At this moment, anyway, in my work, I probably don’t mean what you think I’m saying. It’s a little juvenile, but terribly fun.

Many of your works are created on an incredibly small scale. Can you talk about the choices you make regarding the size of your art and some of the challenges you face in the creation of your smaller pieces?

I think a lot of people who work small will understand that the challenge (for me, anyway) is in scaling up, not down. I’ve been stretching my ‘natural’ size over the years, but I’ve always felt most comfortable in smaller sizes, which feel ‘right’.

You have created artworks that can be found hidden inside objects, such as old matchboxes. What is it that first got you interested in concealing your work in this way?

I think it was two-fold: first, I have a natural inclination towards the small, and particularly towards collections of small things in tiny drawers or boxes. I had a marvelous dollhouse as a child, and the dolls interested me not a bit whatsoever, but the little drawers! With their little forks and knives and cabinets of canned goods! Fabulous. Anyway, second, I was going through a period of frustration a few years ago with the way that our artworks sometimes feel like dead show-pieces, rather than the live beings you manipulate when you work on them, and I was trying to find a way to make a painting continue to ‘work’. Physical interaction of the viewer, and putting the decision of whether or not to conceal the painting in their hands, seemed like one way of rebelling against that. From there, it just grew. They’re terribly fun to do.

You’ve been exhibiting your art for a number of years now. In what ways do you feel you have matured as an artist during this time and how have you seen your work evolve?

I’ve changed immensely. I continue to change. I’m doing very different work than I did a few years ago. I’ve consumed a lot more art and theory in the intervening years that have informed my work a lot. I’m striving to be more political, as I said, but also to be less accessible in a way, more challenging, more expressionistic, less narrative. I want to find a new way to speak with these old media.

As someone with a deep interest in and extensive knowledge of history, can you talk to us about your relationship with art history, and how important you feel it is for an artist to understand what has gone before them?

I have (at least) two minds about it, I’m ambivalent as to how to answer…The short (possibly smart-assed) answer is that it might not matter, I guess, as an artist? I don’t think that nestling one’s work (or oneself) in a linear trajectory of art history necessarily does any good for the artwork at hand. We had a rich, explosive, exciting twentieth-century of art movements and theory to disabuse ourselves of that notion. There are also some Big Questions regarding class and culture that need to be addressed if we’re requiring artworks to be made by artists who ‘understand what has gone before them’. But again, I just don’t think it’s necessary for any particular artwork to be successful. I don’t subscribe to the adage “you have to know the rules to break them”. That’s potentially very exclusive and class/culture-restrictive.

As a human being, however, I think you do you and your society a grave injustice in being ignorant of history (or literature, or politics, or philosophy, or…). I think you maintain that at everyone’s risk.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you first embarked on your journey to becoming an artist?

Not to think of a work’s reception when you make it. Not to let anyone else’s opinion (or your idea of what their opinion might be) or your conception of what ‘should’ be, change anything you do. It takes incredible concentration and dedication to your own goals to achieve anything close to that, I think, and it’ll be a daily struggle until I’m doorknob-dead.

What’s next for Allison Sommers?

One foot in front of the other, as always.