‘Find My Friends: How to Internet and Also Art’ by Lori Nelson

Squirrels. They’re everywhere in Brooklyn, but especially chattering away in my brain, the little devils. I call the not-unique inability to focus for very long, Squirrely Brain or sometimes, Chatter, and picture furry rodents jumping all disorderly from limb to limb on my braintree and half-burying or unearthing ideas here and there, never completing anything before bounding after the promise of a new and interesting nut. I’ve found it harder to get my claws into a book these days, or write like I used to because of the Chatter and, without any professional qualifications, I attribute this problem to the Internet and all its little boxes and machines containing the everpromise of a constantly new nut.

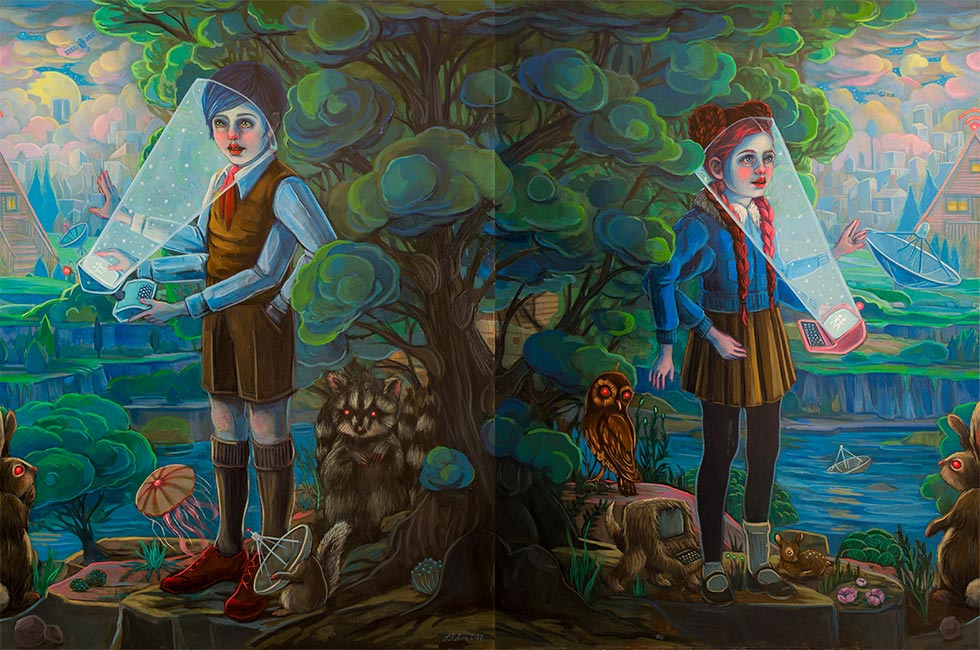

It is in this chattery atmosphere that I created my most recent show at Corey Helford Gallery, ‘Cryptotweens: Find My Friends’.

For the past few years, I’ve developed a cast of tween-aged subjects, Cryptotweens, with cryptid traits like fur, scales, surplus arms, the like, who often also possess powers like laser-beaming, flame-breathing, or just everyday levitating. Recently, though, many of the Cryptotweens have been newly armed with electronic devices and powerful imaginary apps, reflecting my daily observations of my own kids moving throughout the city, faces in their phones. Internet-born youth are so casually adept and fluent with technology that they may as well be the fictional creatures of my own imagination. The apps I create in my work like, ‘Maximize App’, an app that can enlarge any actual object (in this case a porcupine) with a pinch-spread of the fingers, or ‘Back to Nature App’, technology that imposes a bear-populated forest over a girl’s Brooklyn neighborhood, seem inevitable in our current environment of possibility.

Lest my work be interpreted as a screed against technology, however, let me make it clear that I owe much of my career to the darn Internet and I can credit most of my artist-friendships to social media. ‘Find My Friends’ is a real app that we find on our Apple devices whose purpose is to track loved ones as they move about their lives. Firmly rejected by my own children, this app intrigued me, mostly for its somewhat plaintive name that sounds like a wishful plea. The app’s name became the title for my show and for the largest piece in the exhibition, a reversible diptych which shows two subjects in the woods surrounded by wi-fi, satellites, and electronic-eyed forest creatures. In one position, the subjects, a girl and a boy, are back to back, grasping their little computer devices with the ‘Find My Friends’ app symbol illuminated, and searching in the night for each other. When repositioned, the subjects face each otherand, with faces lit by devices, find each other.

It is in the spirit of finding one another through new technology and tools that I approach my latest work, fully knowing that these tools can isolate us and erode in a very significant way our capabilities for concentration and contentedness. I’ve found that I have to tie myself to the mast, so to speak, to resist the call of the Internet, especially when I have work to get done such as I did while preparing for the show at CHG. During the fall and winter before my springtime exhibit, I dumped social media apps off of my phone and had my family leave me alone with our dog and my easel in our cabin in the Catskill forest for weeks. With no car and a pile of firewood and food to see me through some significant snow storms, I created this body of work. The days merged and I pulled all-nighters, unshowered and unimpeded. In the evenings I would connect by the fire with my friends through social media and text. This is how I do art in the era of the Internet.

But what about others?

Like I say, I maintain many of my artist friendships through the Internet and its social media platforms. Diving down the rabbit hole of how to be an artist today and work the technology instead of it working you, I began to wonder how my art colleagues manage. In the spirit of ‘Finding My Friends’, I reached out to four very successful contemporary artists and chatted with them about their experiences with the Internet and art these days. Naturally, I conducted these convos purely in text-form on the Internet.

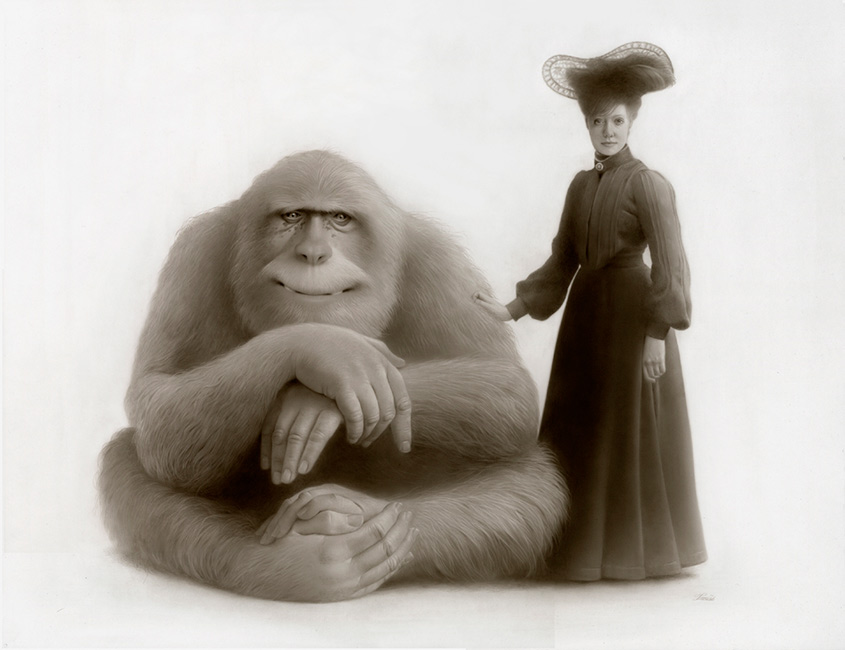

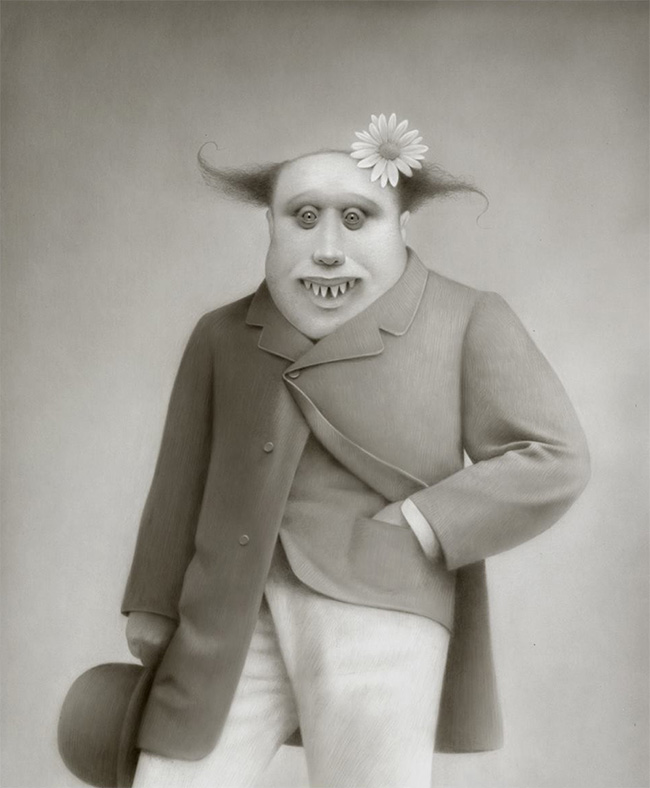

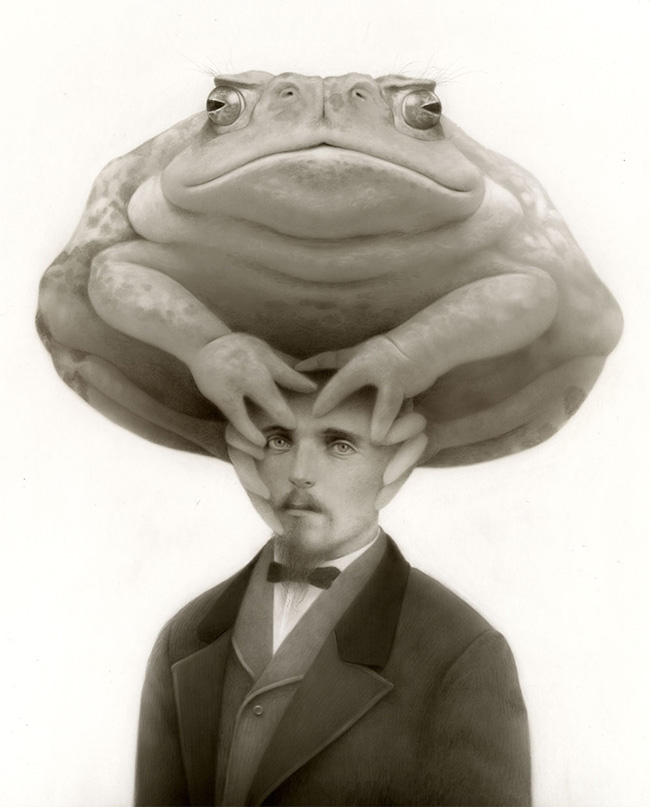

Travis Louie has a solo show in October in Los Angeles at KP Projects (formerly Merry Karnowsky Gallery).

Travis Louie’s paintings look like traditional Victorian sepia-toned photographs of often strange otherworldly creatures. They are at once alien but also recognizable, especially to anyone who has gazed at old photos of immigrant ancestors who seem beautifully lost but often hopeful, too. Travis lives in Woodstock, New York and teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York, but much of what I know about Travis’ personality is gleaned from his smart and ranty posts on Facebook. When I mention that I interviewed Travis to other artists, the response is always, oh, he’s so wise!

I fortuitously messaged Travis mid laundry cycle and he agreed to answer my questions before the dryer buzzer went off about what the Internet has done for (or against) him in his art and how he uses technology.

Travis has been making and selling art since before online marketing platforms really took off and he knows the before and the after. He acknowledged an immediacy that can be helpful in reaching a fan base and in promoting his work, but he spoke about a real old-school desire to have his work viewed in a bricks-and-mortar gallery situation and to be able to personally connect with his audience to explain his process and discuss his work. “In person,” he says, “there is more of a ‘magic trick’ to my work. I like to be able to let people see what my marks look like in person.” He says his work gets misinterpreted online as graphite and that file-size limits can simplify his work. “As far as my brushstrokes and acrylic smudging techniques, it doesn’t read as well as I would like (online).” Even so, Travis’ work does well online and he’s been able lengthen the reach of his work.

But even though he can share his work more broadly today, Travis complains about the ‘fast-culture’ endemic to the online artworld. “The Information Age continues to speed on and the zeitgeist seems to be harder to grasp. Galleries, like clothing designers want to grab hold of the next big thing, but the difference between the two is that one is more informed by the past than the other… If we consider that the conversation of ‘ART’ is informed by the past and communication, or rather the spread of information is at such a lightning pace, we can understand why things are the way they are…’fractured’ as you say.” To Travis, whose subjects and style converse heavily with the past, this speedy, fractured zeitgeist is a little at odds with his work, although he continues to succeed anyway, quite nicely.

When asked about artist-as-art in so much of today’s online culture where the person behind the work can be as significant as the work itself, Travis replied, “Yep, my face doesn’t sell my work, thankfully. I’m lucky that way.” And then the buzzer on his dryer went off and he reportedly went to iron his clothes (Travis Louie is the only artist I know who irons their clothes).

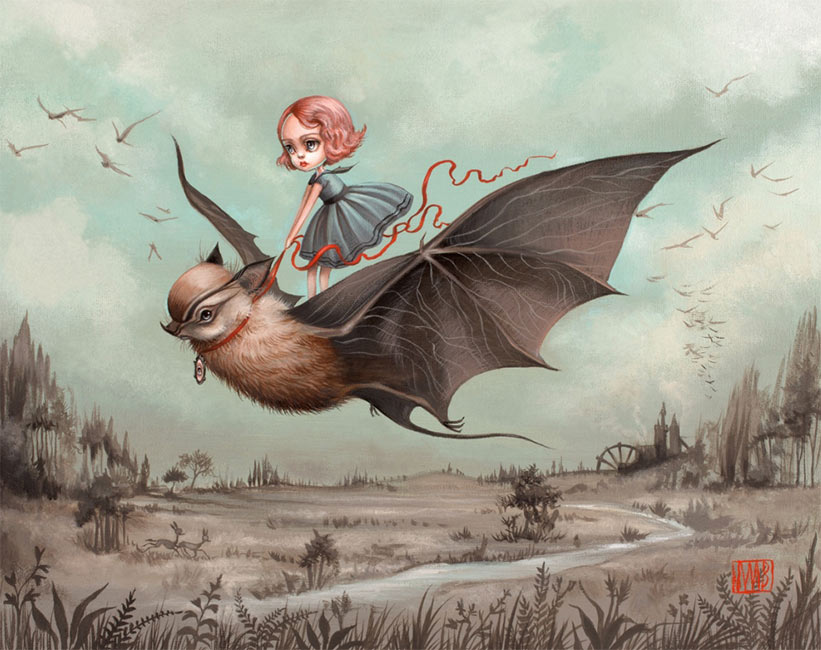

Mab Graves’ solo show “Children of the Nephilim”, three years in the making, opens November 4 at Monster Gallery in Indianapolis.

I knew Mab Graves first through social media and then later, when we showed together in galleries and fell into a fast friendship in real life. Mab is a spritely pink-haired art powerhouse based physically in Indiana but who seems to inhabit social media so powerfully that I sometimes forget that she doesn’t actually live next to me inside my phone. Like Travis Louie, (and me), Mab’s work explores the alien and otherworldly aspects of life by pairing strange, wide eyed creatures and humans in surreal environs. However, Mab’s approach to sharing online, in contrast to Travis Louie’s, is very incorporative of herself, the artist, in the narrative she shares about her life, the people she loves, and her art. Mab’s following on social media is nothing short of cult-like with followers consistently creating fan-art and tributes to their favorite artist. Her work sells out instantly when exhibited.

Mab told me in a text conversation that she felt the Internet had been a game-changer for artists, handing them the “power to connect with our viewers, buyers, collectors, and friends, without relying on someone higher up in the food chain (dealers or galleries) to believe in us or give us a chance. If we do the work (and it’s a lot!) we can get found on our own. It’s incredible. This generation of artists has more power in that sense than any other in history.”

Having grown up without much media exposure, Mab doesn’t find the call of the Internet to be a problem or too distracting. She uses social media as a very finely honed tool to connect with her fans and is quite precise in how she implements it. Earlier in her career, Mab kept her posts, “strictly business” and on-topic about her work, shying away from the personal. She started noticing though that she connected more with artists who let viewers see their studios and inspirations and so eventually she became braver, believing that her life was a big part of her art making. Little by little, Mab got more personal, showing her own delightfully messy space, her relationship with her young nephew (creating the #auntieshavethebestjobs hashtag), and eventually, revealing a medical battle that knocked her pretty low and had her hundreds of thousands of followers extremely worried, and eventually, simultaneously relieved when she felt better.

I’ve noticed that Mab is very responsive in her social media, answering in a personal way many of the questions and comments followers make when she posts. This can be surprising to fans who are used to the post-and-dash ways of many successful artists who seem to dutifully post their beautiful work and consider the job done. Mab’s interactivity goes a long way in explaining the fidelity her fans feel for her, aside from their love for her art. They don’t just admire Mab’s work, they have a relationship with Mab, something that Mab underscores, saying, “I feel like sometimes the reason we have social media gets lost or forgotten. It’s very easy to become self- focused and forget the power it has.” She emphasizes the ‘social’ in social media and approaches everything in a sharing way.

In the spirit of generosity, Mab one-upped herself in our chat and offered to reveal her self-imposed rules for social media that have helped to create the powerful online presence she enjoys. I was all ears!

Mab’s Social Media Cardinal Rules:

1. One in every ten posts has to be about someone else and has to be personal. Not just, “check out this person”, but, “I love this person and here’s why.”

2. No more than a couple process shots. Some artists really kill it with a million shots of works-in-progress and you can tell they are distracted from the process and are getting hooked on the praise.

3. One in every ten posts is a shot of my studio or something that inspires me.

4. One in every ten posts is personal, with my feelings or perspective on something. But no whining. It has to be uplifting, even if it’s about something sad.

You can bet that I’m paying attention to those rules now. In my own social media, I’ve shied away from being very personal, thinking that people are there for the work, not my lifestyle. Not being quite as photographable as Mab Graves, that might be a little accurate, but I do believe there is room for more generosity and reciprocity on the social media platforms by many artists.

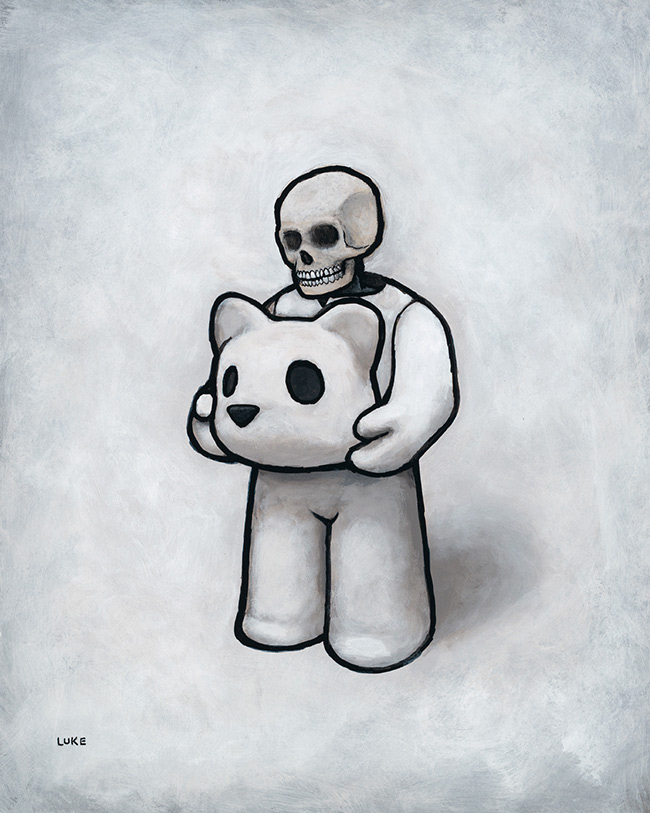

Luke Chueh has a December solo show in Los Angeles at Corey Helford Gallery, and some upcoming toy releases with Munky King.

I was aware of Luke Chueh’s work before I met him. His paintings of anthropomorphic bear or bunny-man creatures have become iconic, and toy collectors rabidly seek his signature bear figures (or perhaps it’s a guy in a bear-suit?) with their head-in-hands postures of despair. I came to like his work even more after talking with him at length recently at a gallery opening (ok, my gallery opening.) In person, after a little warming up, Luke speaks from the heart in a disarmingly honest way about art and life, often closing his eyes while he talks, painstakingly making sure that he’s getting the words right for whatever he is describing while bracing for whatever may come from that vulnerability. He seems to willfully shed a protective social skin and be real. But that’s in person. Luke online is quite another bear.

Scrolling through Luke’s social media account, I found it to be pretty businesslike, all about the product. You’re not going to see his messy studio or times spent with loved ones. This doesn’t seem to affect his fanship though, I think fans must find plenty of Luke within his art which, for being so spare and simple, can be exacting in its heartbreak. The disparity between IRL Luke and online Luke made me curious. I decided to message him about how he feels about the Internet and social media in regards to his art and his online presence.

He began by telling me about how the Internet initially really boosted his career in the early 2000’s, getting exposure for his work and getting him out in the world. “However,” he continued, “between 2003 and now, the Internet has changed significantly. Social media is exhausting and I’ve scaled back on how much time I dedicate to updating my Internet presence. If I was going to guess, I’d like to say my time is a little more consumed with work, but maybe ‘cause I’m just older and tired. [Or] maybe the real reason why is because the way we absorb information on the Internet has changed.” He goes on to note that the Internet, ever faster in its delivery of information, has moved away from a primarily thoughtful blog and website focus to the more immediate post-and-response social media platforms, the result being that, “I got more and more discouraged by social media. Maybe because I don’t go out as much as the people I follow do?”

I mentioned that a lot of posts are really just posturing.

“Yeah, I know it’s posturing,” he replied, “but it still reminds me that I don’t have a social life.I have a love hate relationship with crowds. It’s like frosted mini wheats. The kid in me loves the excitement, the adult in me wants to die.” This is interesting, considering Luke makes a lot of public appearances for his work. “I often hear people saying they’re surprised I’m so easy to talk to,” he said. “But I think that’s built up over 10 years of ‘training’. I put a pretty good mask on when it comes to ‘cons and shows (but to deny that I have a happy social side is to deny a part of my being).”

I suggested that this all fits pretty neatly with the work he makes to which he replied, “approachable facade with gut wrenching issues if you just scratch below the surface. Yay.”

“That’s why people love you though,” I posited.

“I guess so. As long as my issues are entertaining.” he replied, to which we both typed at the same moment,

“Or relatable.”

Luke posts about his work on social media at “strategic times of the day and only content I think my fans want to see.” His online self is largely distinct from his person, maintaining a barrier of sorts for the guy behind the art and inside that bearsuit.

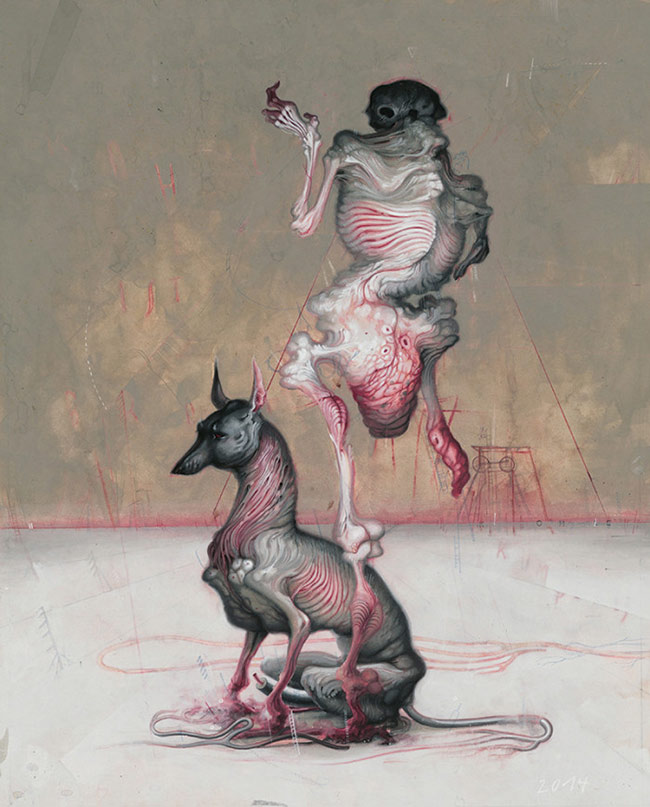

Allison Sommers is part of a 3-person show opening 5/25 at Antler Gallery in Portland, Oregon.

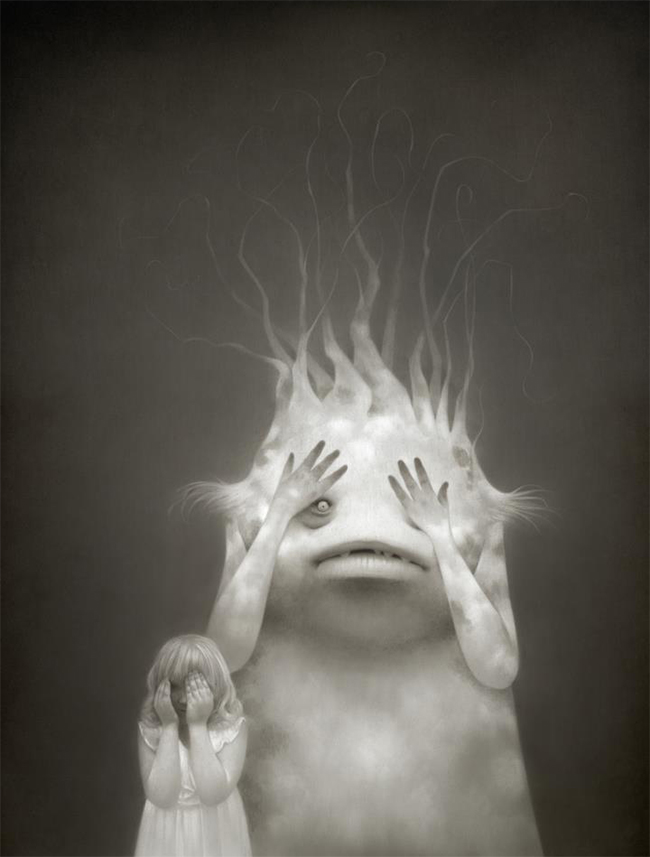

I first knew Allison from showing with her at the iconic Brooklyn gallery, The Cotton Candy Machine. Allison’s work presents an expertly balanced juxtaposition between beautifully handled gouache on found, often antique, surfaces and a visceral, sometimes gruesome subject. The work’s intrigue often lies in the inability for the viewer to distinguish exactly what Allison has painted, leading to the resulting impression that entrails, beasts, and blood were involved. But Allison is never explicit and the viewer is left with the feeling that they’ve peeped something horrible, although they cannot accurately describe what they’ve witnessed.

Allison falls into the category of Artist-as-Art and admittedly strives to curate her real-life existence accordingly. That said, she herself is not the commodity displayed in her social media postings even though the actual very romantic figure who is Allison would be easily commodified. She doesn’t post many selfies, but I’ve often been struck by her carefully curated vintage clothing and old-fashioned accessories when I’ve seen her.

Not surprisingly, Allison is a little conflicted about social media as she described to me over Messenger when we discussed the Internet and artists.

“I don’t like it’s influence, I don’t like its permeation of all layers of culture, and I don’t like the way that we’re tailoring ourselves, our work, our whatever to it. These complaints are, I’ll admit, just New Media complaints and could be said of television or radio if they were new. Just happens to be the current wall against which to bang my old-fashioned head. And I am old-fashioned. My parents somehow made me a baby-boomer. Blah, blah, admission that I still use a computer everyday. We’re speaking over Facebook, etc.”

Nevertheless, Allison enjoys quite a following online, her success owing as much to the colorful, floral wording with which she laments politics and current events as to the art she posts. “But don’t expect me to be taking a rash of selfies anytime soon.” she quips.

She continues, “I’m doing very little online commodification of the work-as-interacts-with-artist. There aren’t any photos of me languishing on a well-lit sofa in lingerie in front of my paintings. I don’t spend any thought at all in ‘branding’ on social media. What you see is what you get all the way. But I have, in a very romantic-old-fashioned-nineteenth-century way, spent a lot of time cultivating self- as-artist in real life. That sort of gardening is very old hat indeed (I always think of Oscar Wilde in those photos, draped in velvets and fur and being gorgeously ridiculous) and I’ve been grooming that particular commodity (if we must call it that, blech) my whole life. Where it intersects with digital life is merely a byproduct of using social media. The artist-as-theatrical-role is an invention that everyone is getting. I’m not living some sort of doubled life.”

Allison’s embodiment of her work seems ideal to me, beautifully living and breathing her ideas in a global way, not in a staged way. Even with her broad approach to her artistic identity, however, Allison, like all of us, hears the siren song of the Internet and it’s endless array of distractions. “I set pretty rigid boundaries with the Internet, etc. because otherwise I get swallowed.”

The exercising of moderation and self-control consistently rose to the surface throughout my discussions about being an artist in the age of the Internet. I personally recommend hobbling your apps if you are trying to complete a project. Show the chattery brain-squirrels the door. I find that deleting apps from my phone and laptop and making them available only on our old desktop machine can return me to my productive self. When my goals are met, I gather up all my apps again and catch up with the art-promotion and online fraternizing because social media is integral to my career and social life. Without the Internet, as I explained to my friend, Mab, I could not ‘find my friends’ so easily.

“So!” I told Mab, “My conclusion about the Internet: How would I be able to type/chat with you without it? I would be here scribbling questions to an imaginary friend. Instead, I have you! It’s a good time to be alive.”

“It’s an incredible era for artists”, replied my friend. “There are a lot of negatives, but the positives totally outweigh them in my opinion.”